Case Report - Clinical Practice (2019) Volume 16, Issue 2

The evolving landscape in the management of gastric metastases from melanoma: a case series

- Corresponding Author:

- Michele Guida

Department of Medical Oncology

National Cancer Research Centre “Giovanni Paolo II”, Bari, Italy

E-mail: micguida@libero.it

Abstract

Background: The stomach is a very unusual site of metastasis from melanoma. Due to the few reports, we collected a case series in order to focus their endoscopic, clinical and biological features and to explore the therapeutic outcomes.

Methods: We collected 9 consecutive cases of gastric localization of metastatic melanoma. Results: All patients presented a long, nonspecific and vague history of gastric symptoms often cured as gastritis. The endoscopic features included multiple smooth black spots, ulcerated polypoid lesions or a wide neoplastic infiltration. BRAF status was mutated in only 1 patient while an NRAS mutation was found in 3 cases. Palliative gastrectomy was performed in 4 of 9 patients resulting in a good control of symptoms. The median survival in patients underwent gastrectomy was 25 months vs 4 months in non-surgically treated patients. Conclusions: We emphasize that physicians should be aware of the possible gastric involvement in patients with a history of melanoma and should suggest to promptly perform an endoscopic evaluation in symptomatic patients. Gastrectomy should be offered to all patients for palliative intent and to allow to plan systemic therapies recently enhanced with new and more effective drugs.

Keywords

Melanoma, gastric metastases, gastric surgery, gastric endoscopy

Introduction

The incidence of melanoma has continuously increased in the last decades. Early diagnosis and improved surgery management have limited mortality, but in advanced disease, prognosis remains poor. However, since 2011 a new era in the treatment of metastatic melanoma is beginning, thanks to robust advances in our understanding of the molecular biology of this neoplasm and of the complex role of host immunity. New drugs including target and immunomodulatory agents are changing the outcome of advanced melanoma [1,2].

As known, in the metastatic phase, melanoma is able to spread to every part of the body. Intestinal localization is a common occurrence in disseminated disease. Nevertheless, localization to the stomach is a very unusual event and accounts for only approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal localizations with about 1.5 % of all metastatic disease in post-mortem case-records [3].

Primary gastric melanoma is even more infrequent with only a few cases reported in the English literature [4,5]. Melanoma involving the stomach seldom causes relevant early symptoms and this is why diagnosis is generally tardy. Moreover, the endoscopic and pathological features of gastric metastases from melanoma are limited and restricted to single case reports.

We report 9 cases of patients with a long and vague clinical history of gastric symptoms who presented different endoscopic, biological and clinical patterns of gastric metastases from cutaneous melanoma. Finally, we review literature data and discuss the role of palliative surgery in order to control the clinical complications and to plan further systemic therapies recently enhanced with new effective drugs.

Methods

We retrospectively revised clinical, endoscopic and histological features of nine consecutive patients with gastric localizations of melanoma referred to the National Cancer Research Centre “Giovanni Paolo II”, Bari, Italy from 2006 to 2018 (TABLE 1). All the patients but one previously underwent surgical resection of primary skin melanoma. The median time interval between skin melanoma diagnosis and gastric involvement was 2 years. One patient showed a synchronous liver, lung, bone and gastric involvement by an unknown primary melanoma.

| Features | Cases | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Sex | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male |

| Primary melanoma | skin | skin | skin | skin | skin | skin | skin | skin | unknown origin |

| Age at first diagnosis (ys) | 46 | 64 | 59 | 78 | 45 | 55 | 72 | 53 | 52 |

| Age at gastric involvement (ys) | 52 | 66 | 63 | 79 | 47 | 56 | 82 | 60 | 52 |

| Symptoms | - epigastric discomfort - nausea and vomiting |

- abdominal pain - weight loss - weakness |

- abdominal pain - weight loss - haematemesis |

- appetite loss - nausea and vomiting - epigastric pain |

- none | - weakness - melena - epigastric pain |

- epigastric discomfort | - abdominal pain - weight loss |

- melena - epigastric discomfort |

| Abnormality of Lab tests | none | none | none | Hgb 8.9 g/dl | none | Hgb 6.0 g/dl | none | Hgb 6.4 g/dl | Hgb 8.9 g/dl |

| Imaging | none | none | none | lesion with a low 18F-FDG-uptakeat at PET/CT |

irregular gastric wall at CT scan | irregular gastric wall at CT scan | lesion with a high 18F-FDG uptakeat at PET/CT | none | none |

| BRAF status | wild type | wild type | wild type | wild type | V600E | wild type | wild type | wild type | Wild type |

| NRAS status | wild type | wild type | wild type | wild type | wild type | wild type | Q61K | Q61R | Q61R |

| Systemic treatment | CDDP + DTIC + IFN | 1st line: DTIC + IFN 2d line: Fotemustine 3th line: TXT |

1st: line: CDDP + DTIC 2d: line Fotemustine |

none | Vemurafenib | 1st line: DTIC 2d line: Ipilimumab |

1st line: Ipilimumab 2d line: Nivolumab |

Nivolumab | Nivolumab |

| Gastrectomy | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| OS from metastatic disease | 8 | 36 | 30 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 3 |

| OS from gastric involvement | 8 | 24 | 19 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 3 |

TABLE 1: Clinical features of patients.

Results

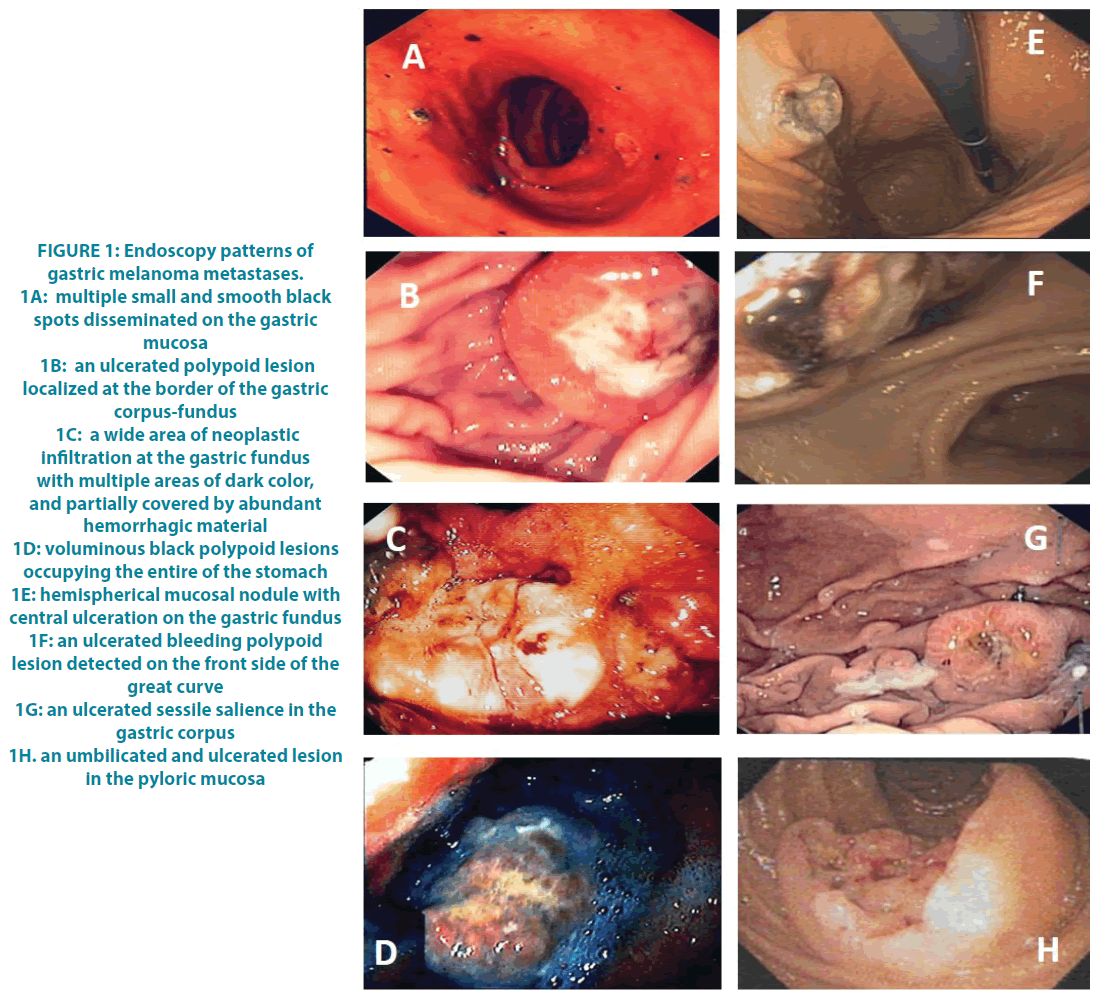

All our patients complained of various gastrointestinal symptoms which ranged from vague discomfort in the epigastric region through sporadic episodes of nausea and vomiting, anorexia, weight loss and the occurrence of haematemesis and melena. Laboratory tests in 4 cases revealed the presence of an iron deficiency anemia due to gastrointestinal blood loss. All patients underwent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) which allowed to confirm the clinical suspicion and to obtain a histological diagnosis. Very different endoscopic patterns were observed (FIGURE 1A-H). Case 1: the presence of multiple smooth grey-black nodules disseminated on the gastric mucosa, especially in the pyloric antrum, of a size between 0.5 and 2 centimeters in diameter. Case 2: a large polypoid lesion with a smooth surface, partially ulcerated of about 2.5 cm in diameter localized at the border of the gastric corpus-fundus. Case 3: a wide scar area of neoplastic infiltration localized at the gastric fundus and extending along the greater curvature. Case 4: two voluminous black polypoid lesions of about 6 and 4 centimeters in diameter occupying the entire fundus of the stomach. Case 5 and 9: multiple nodules on the gastric mucosa with hemispherical appearance and central ulceration. Case 6: an ulcerated bleeding polypoid lesion in the front side of the great curve of the stomach. Case 7: an ulcerated sessile salience of about 2 centimeters in diameter in the gastric corpus. Case 8: two ulcerated and umbilicated lesions on fundus and pyloric mucosa. The imaging techniques supported the evidence of gastric lesions in 4 cases, including 2 patients in which the PET/ CT scan showed a high uptake of 18F-FDG, and 2 patients with a CT scan reporting an irregular thickened wall along the small gastric curve.

Figure 1: Endoscopy patterns of gastric melanoma metastases.

1A: multiple small and smooth black spots disseminated on the gastric mucosa

1B: an ulcerated polypoid lesion localized at the border of the gastric corpus-fundus

1C: a wide area of neoplastic infiltration at the gastric fundus with multiple areas of dark color, and partially covered by abundant hemorrhagic material

1D: voluminous black polypoid lesions occupying the entire of the stomach

1E: hemispherical mucosal nodule with central ulceration on the gastric fundus

1F: an ulcerated bleeding polypoid lesion detected on the front side of the great curve

1G: an ulcerated sessile salience in the gastric corpus

1H. an umbilicated and ulcerated lesion in the pyloric mucosa

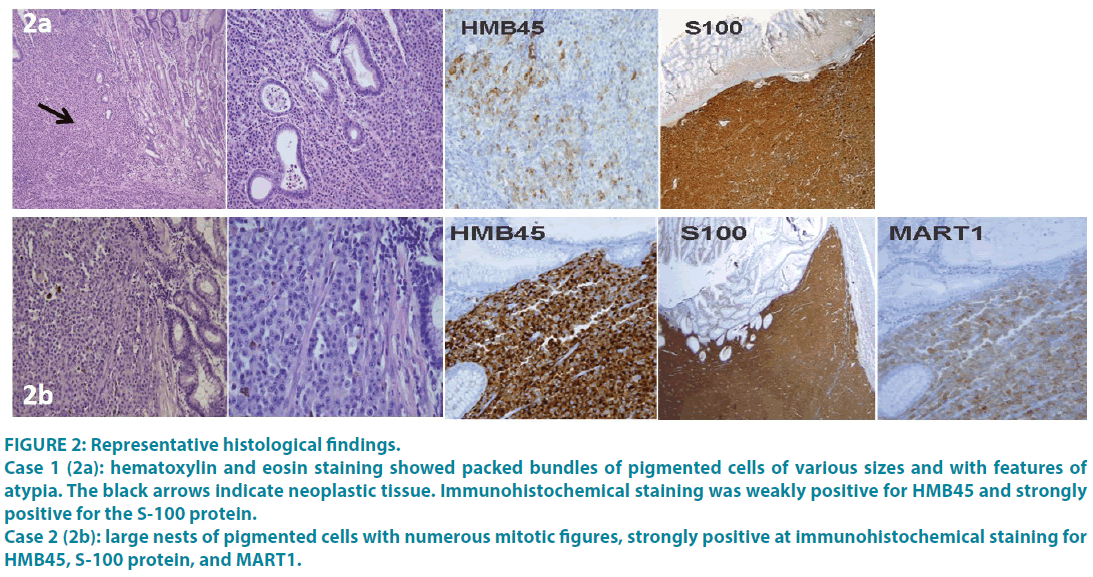

In all cases, multiple biopsies were performed and the histology was compatible with the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma. Immunohistochemistry revealed a homogeneous staining of the neoplastic component for the S-100 protein and less regular for HMB45 and MART1in all the cases (FIGURE 2A and 2B). Moreover, the molecular evaluation of BRAF and NRAS status performed in all the cases revealed the presence of NRAS mutation in 3 patients, a BRAF V600 mutation in one patient and the absence of driver mutations in the remaining 5 patients.

Figure 2: Representative histological findings.

Case 1 (2a): hematoxylin and eosin staining showed packed bundles of pigmented cells of various sizes and with features of atypia. The black arrows indicate neoplastic tissue. Immunohistochemical staining was weakly positive for HMB45 and strongly positive for the S-100 protein.

Case 2 (2b): large nests of pigmented cells with numerous mitotic figures, strongly positive at immunohistochemical staining for HMB45, S-100 protein, and MART1.

In all patients, gastric involvement was metachronous with a broader melanoma spread and all except one received systemic therapy. Four of 9 patients in our series received a radical or partial gastric resection with palliative intent resulting in a good control of gastric symptoms such as pain, anemia, and anorexia. The remaining 5 patients did not undergo surgery due to the absence of an immediate life risk related to the gastric localization and they were treated with systemic therapy for stage IV melanoma. However, in our series gastrectomy was associated with a higher number of treatments and a longer median overall survival both from metastatic status (25 months vs 4 months) and from gastric involvement (19 months vs 4 months).

Discussion

The stomach is an unusual site of metastasis from any type of cancer with breast and lung cancer being the most common primary source followed by esophageal, kidney neoplasms and then melanoma [3-6,7].

As is known, melanoma is able to spread to every part of the body and its tropism for the gastrointestinal tract is particularly pronounced. Nevertheless, gastric localization is very rare.

Clinically, gastric metastases could be silent for many years or could only give vague signs mimicking chronic gastritis which is often underestimated by both patients and physicians causing a delayed diagnosis.

Sideropenic anemia or bleeding, dyspepsia, and epigastric pain represent often the first clinical manifestations of stomach involvement [3,6,7]. Fortunately, in all of our patients, the gastric symptoms were present early allowing the diagnosis at an early stage.

Endoscopy is the main tool for the diagnosis of gastric metastases even if the endoscopic findings could mimic any type of primary gastric tumor in an early or advanced form. Features could include polypoid masses, nodules, ulcers and less frequently dark flat macules. A typical feature of melanoma metastases at gastroscopy is a sub-mucosal, melanotic or normal stained nodule that is umbilicated, depressed and ulcerated on the top, variously called “doughnut” bull’s eye” or “volcanoid or crateriform lesion”. These aspects were present in five of our cases (case 2, 5, 6, 7 and 8). Regarding the topographic localizations in the stomach, metastatic lesions occurred more frequently in the body and the fundus of the stomach and more often are reported to be solitary than multiple [3-6,7]. Our series includes 4 single gastric metastases out of 9 cases with gastric fundus involvement in 7 cases. The key diagnostic role of endoscopy is also linked to the need to provide the pathologist with sufficient bioptic material to allow an accurate histological diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis between primary gastric cancer and metastatic lesions is often full of difficulties. Sometimes, the suggestive macroscopic features with grey-black smooth nodules support the diagnosis. Hematoxylin and eosin staining are often able to confirm the diagnosis of melanoma metastases showing large nests of epitheloid pigmented or nonpigmented cells with numerous mitotic figures, hyperchromatic nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemistry often revealed the staining for the S-100 protein, MART1, and HMB45.

Regarding treatment, there is no guideline for proper therapy for gastric metastases from melanoma. It should be noted that gastric localizations rarely represent the sole site of relapse, and more often they appear in a widespread context. Thus, systemic therapy is generally utilized. At present, genetic analysis to locate the driver melanoma mutations such as BRAF V600 and NRAS is essential in the selection of the most appropriate therapy for every single patient. There are no previous data in the literature about the rate of mutation in melanoma that metastasize to the stomach. In our series, we report only 1 case of BRAF mutation which is lower than the rate of about 50% for cutaneous melanoma reported worldwide. The absence of this driver mutation does not allow the use of target therapy which is usually associated with high rate and fast response and restricting the therapeutic choice to the check-point inhibitors and chemotherapy.

On the contrary, the presence of NRAS mutations, well known for their worse prognosis [8], was observed in 3 out of our 9 cases (33%) that is higher than the 10% rate generally reported for stage IV melanoma [9]. There is no targeted therapy for NRAS mutation, thus these patients, like the BRAF wild-type carriers, are treated with PD1 or CTLA4 inhibitors alone or in combination [1]. In this scenario, the surgical treatment could play an important role in both palliative intent and to allow to plan further systemic therapies. Radical gastric resection can be planned as a safe and appropriate option for the control of symptoms and for the improvement of the quality of life of patients as well as for gain a time to allow the systemic therapy an effective anti-melanoma activity. In our series, the longer OS observed in patients treated with surgery is in accordance with the few retrospective reports, demonstrating that surgery can also extend life expectancy (TABLE 2) [7,10-14].

| Reference | Total of patients | N. of patients treated with surgery | Median OS (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes surgery | No surgery | |||

| Gallino G., 2001 | 9 | 6 | 21,6 | 3,6 |

| Campoli P.M.O., 2006 | 3 | 0 | 4.75 | - |

| Liang K.V., 2006 | 2 | 2 | 5 | - |

| Trouillet N., 2010 | 2 | 0 | 2 | - |

| Kim G.H., 2015 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| Our series | 9 | 4 | 25 | 4 |

Table 2: Case series of patients with gastric metastases from melanoma.

Conclusion

Gastric metastases from melanoma are a rare but underdiagnosed entity. Due to their rarity and a limited number of published reports, our case series may be a contribution to focus on clinical, biological, endoscopic and treatment features. We underline the need to be aware of the possibility of gastric involvement and to carefully monitor patients with a history of melanoma who complain of dyspeptic disorders or vague gastric symptoms. Endoscopic examination with multiple biopsies is crucial to define diagnosis and to plan further therapeutic approaches. Thus, endoscopy should always be proposed to a patient with gastric discomfort and a previous diagnosis of melanoma.

With the gradual improvements in survival for melanoma patients, metastases in the stomach could be encountered more frequently. This scenario outlines the need to build studies in order to define the proper treatment of these patients.

Gastrectomy should be offered to all patients for palliative intent and to allow to plan systemic therapies recently enhanced with new and more effective drugs.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Financial support

Sabino Strippoli was supported with a research grant by “Associazione ONLUS Maria Ruggieri”.

References

- Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C. Melanoma. Lancet. 392(10151), 971-984 (2018).

- Guida M, Tommasi S, Strippoli S. The search for a melanoma-tailored chemotherapy in the new era of personalized therapy: A phase II study of chemo-modulating temozolomide followed by fotemustine and a cooperative study of GOIM (Gruppo Oncologico Italia Meridionale). BMC Cancer. 18(1), 552 (2018).

- Oda, Kondo H, Yamao T, Saito D, et al. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy. 33(6), 507-510 (2001).

- Phillips O, Higdon A, Colaco R, Fish H. Primary Mucosal Melanoma of the Stomach.Case Rep. Gastrointest. Med. e6040693 (2018).

- Rai MP, Nemakayala DR, Kandola SK, Sharma M. Primary gastric melanoma: a rare presentation. BMJ Case Rep. e224914 (2018).

- De Palma GD, Masone S, Rega M. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: clinical and endoscopic feautures. World J. Gastroenterol. 12 (45), 7326-7328 (2006).

- Namikawa T, Hanazaki K. Clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes of metastatic tumors in the stomach. Surg. Today. 44(8), 1392-1399 (2014).

- Jakob JA, Bassett RL Jr, Ng CS. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 118(16), 4014–4023 (2012).

- Lee JH, Choi JW, Kim YS. Frequencies of BRAF and NRAS mutations are different in histological types and sites of origin of cutaneous melanoma: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol.164(4),776-784 (2011).

- Gallino G. Belli F, Ditto A, et al. Surgical treatment of gastric m etastases from cutaneous melanoma: experience of the National Cancer Institute of Milan. Tumori. 87(4), 229-31 (2001).

- Campoli PMO, Ejima F H, Cardoso DM, et al. Metastatic cancer to the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 9(1), 19-25 (2006).

- Liang KV, Sanderson SO, Nowakowski GS, et al. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Mayo Clin. Proc. 81(4), 511-516 (2006).

- Trouillet N, Robert B, Charfi S, et al. Gastric metastases. An endoscopic series of ten cases. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 34(4-5), 305-309 (2010).

- Kim GH, Ahn JY, Jung HY, et al. Clinical and Endoscopic Features of Metastatic Tumors in the Stomach. Gut Liver. 9(5), 615-22 (2015).