Review Article - Imaging in Medicine (2011) Volume 3, Issue 3

Latest advances in cone-beam CT for bladder radiotherapy

Victoria A Harris1*, Fiona MA McDonald1*& Robert Huddart†1

1The Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Foundation Trust & Institute of Cancer Research, Downs Road, Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5PT, UK

- *Corresponding Author:

- Robert Huddart

The Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Foundation

Trust & Institute of Cancer Research Downs Road

Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5PT, UK

E-mail: robert.huddart@icr.ac.uk

Abstract

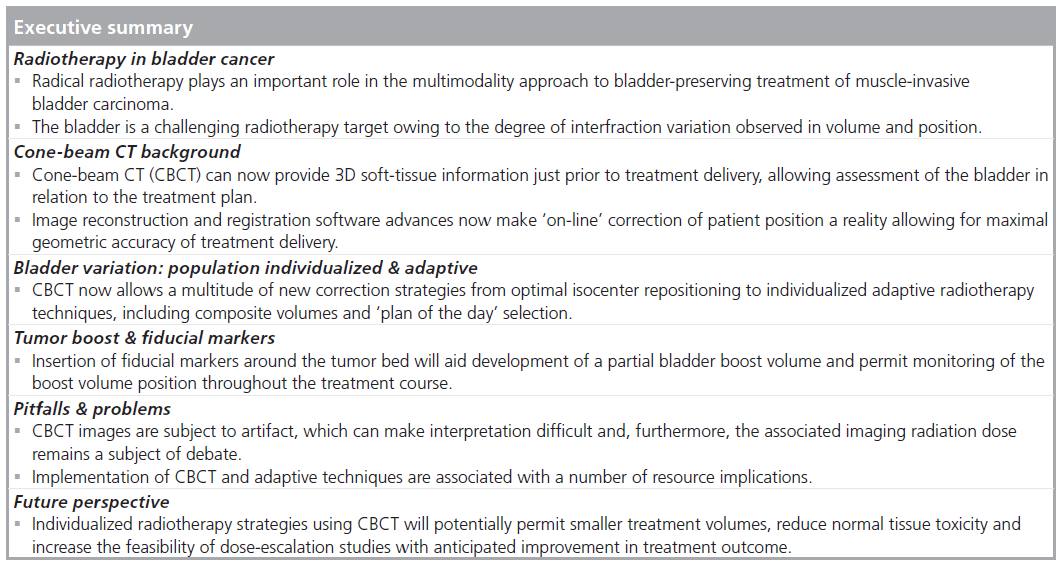

Bladder cancer is a common disease that can be effectively treated using radiotherapy. However, accuracy of radiotherapy is limited by movement of the bladder both between and during radiotherapy fractions due to filling and external factors. Cone-beam CT (CBCT) allows bladder size and shape to be analyzed immediately prior to treatment to ensure it is accurately encompassed within the radiotherapy treatment field by moving the treatment couch. CBCT has also allowed development of adaptive radiotherapy techniques that adjust the radiotherapy plan to account for changes in bladder filling and position, enabling maintenance of tumor coverage while minimizing radiation to nearby normal tissues. In this article, we explore the use of CBCT and how it has enabled the development of these advanced radiotherapy techniques.

Keywords

bladder cancer; cone-beam CT scan; image-guided adaptive radiotherapy

Radiotherapy in bladder cancer

Bladder cancer is a common disease and causes significant mortality and morbidity. A total of 12,100 cases are diagnosed per year in the UK, of which 20% are muscle invasive at the time of diagnosis [101].

Radical cystectomy is regarded by many as the ‘gold-standard’ therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer [1]. Surgical removal of the bladder may result in local control, but patients will need reconstructive bladder surgery or an ileal diversion, and a small proportion of patients go on to develop local relapse of disease [2,3]. Although complications of radical cystectomy have decreased as surgical techniques have advanced, the potential for early and late morbidity and mortality remains [4]. Furthermore, cystectomy is unsuitable for a significant number of patients owing to coexisting medical problems (often smoking related such as cardiac dysfunction or chronic airways disease), by virtue of age/performance status or the pathological and/or anatomical nature of the tumor [5].

In these patients and in those who do not wish to have major surgery and urinary diversion, radical radiotherapy (RT) can be used as an alternative to cystectomy. RT, when successful, can result in cancer cure and leave an intact functional bladder. It does suffer from the problem of treatment-related toxicity and that durable disease control is only achieved in approximately two out of three patients [6], with those failing needing salvage cystectomy. No published randomized trials have directly compared RT alone to surgery alone and a UK trial designed to answer this question closed early due to poor patient recruitment [7]. In the absence of randomized data, the relative results of surgery and RT have been much debated. In modern series, utilizing 3D conformal RT techniques, 5-year survival with radical RT alone is 51% [8], which is similar to that achieved in surgical series [9]. A recent UK series reported similar survival for RT and surgery [10].

Using chemotherapy both in the neoadjuvant setting [11] and also concomitantly [6,12] with RT has shown evidence of improved outcomes; however, little attention has been previously paid to the technical aspects of RT. The emergence of new technologies, in particular, cone-beam CT (CBCT) scanning, will provide solutions to some of the challenges of RT planning and delivery for bladder cancer.

What are the challenges?

As with all RT treatment, the aim is to deliver an individualized treatment plan as accurately as possible. Treatment plans deliver the highest possible dose to the tumor but at the same time must effectively avoid nearby normal tissues, thus reducing the possibility of acute and late side effects.

Target coverage

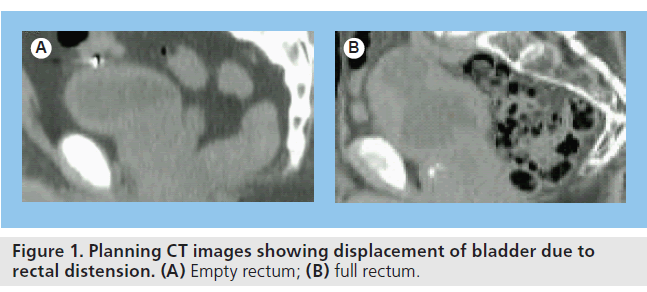

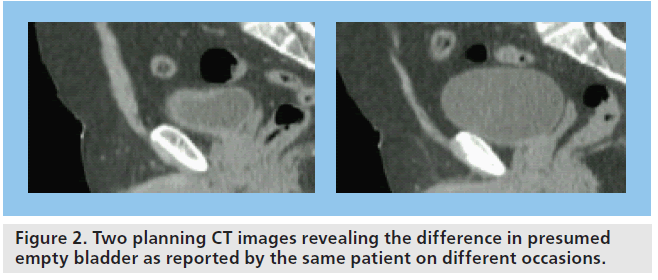

The greatest challenge with bladder RT is due to the variation in shape and size of the bladder during the course of treatment. The bladder can be displaced between fractions due to rectal distension (Figure 1) and the size changes due to continual filling of the bladder during treatment (Figure 2). Adaptation of treatment plans to take these forms of movement into account would increase treatment accuracy.

Normal tissue toxicity

Whole-bladder RT results in a large pelvic volume being irradiated with consequent irradiation of neighboring normal tissues. Nearby structures, particularly the small bowel, rectum and femoral heads, limit the dose that can be given to the bladder owing to their lower tolerance to radiation [13]. By more accurately identifying the area to be treated at the time of treatment planning and again immediately before treatment delivery, it is anticipated that normal tissue toxicity experienced by patients could be either reduced or maintained while the dose delivered to the tumor is increased.

CBCT: background

Target verification

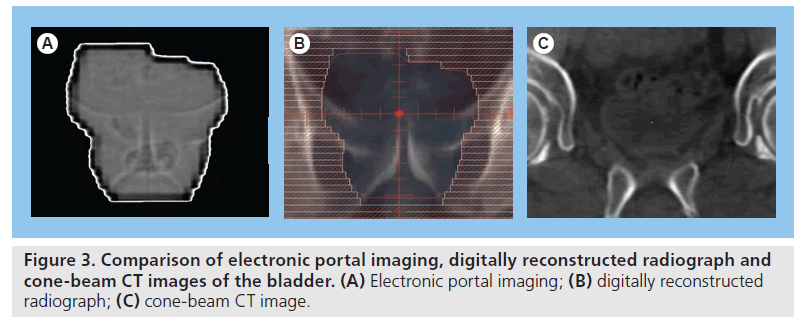

At the time of treatment delivery, traditionally, patients receiving bladder RT are aligned in the treatment position relative to the linear accelerator (linac) isocenter (the point in space within the RT target from which set-up measurements/ adjustments are made) using wall-mounted lasers in the treatment room, which are directed to skin tattoos on the patient. Invariably, use of surface marks as a surrogate for underlying internal anatomy is associated with a degree of set-up error. Until recently, the standard approach for set-up verification was to match the bony anatomy of a treatment image derived from the treatment beam (mega voltage [MV] portal images) with a digitally reconstructed radiograph derived from the planning CT scan. The major drawback to portal imaging is that the image contrast only permits assessment of bony anatomy (Figure 3) rather than soft-tissue structures. Treatment delivery based on bony anatomy is only accurate if the target maintains a stable relationship in relation to the bony anatomy from the planning stage throughout the course of treatment. If not, soft-tissue definition is required to optimize accurate verification of the target position prior to treatment delivery.

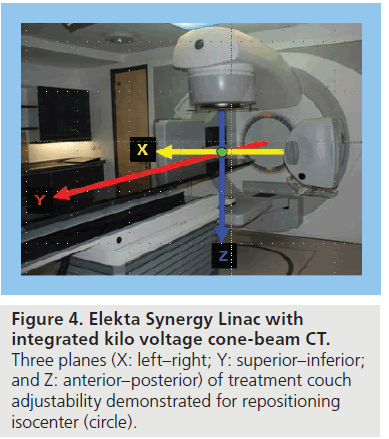

Cone beam CT is a relatively new technology allowing 3D volumetric images to be acquired and reconstructed following a single linac gantry rotation with the patient in the treatment position [14]. Due to the volumetric nature of CBCT acquisition, the images are subject to a higher degree of scatter than diagnostic CT and, consequently, the image quality is not quite as good. There are two approaches to integrating CBCT into the linear accelerator for image acquisition: one uses the MV treatment beam and electronic portal imaging detector (EPID) to produce MV CBCT images; the other approach uses a gantry-mounted kilovoltage (kV) source at a 90o angle to the treatment beam, opposite an additional EPID (Figure 4). The significant advantage of kV CBCT is the improved image contrast produced by lower-energy beams and, thus, improved visualization of soft-tissue structures compared with MV CBCT [15].

Correction strategies

At the time of treatment delivery, the objective is to accurately deliver the planned dose distribution to the target. In bladder RT, the standard strategy to correct for geometric discrepancy between the planned and delivered dose distribution has been with ‘off-line’ assessment. An error each day is usually considered to consist of two components: a ‘systematic’ component due to a persistent difference in positioning between planning and treatment and a ‘random’ component due to day-to-day fluctuations. Taking verification images daily for several days allows off-line assessment of whether there are any persistent (systematic) set-up errors that can then be adjusted before subsequent treatments. This process does not account for random errors; however, assessment of verification imaging ‘on-line’ prior to treatment delivery provides the potential for intervening and correcting for both systematic and random set-up errors caused by daily variation, thus maximizing geometric accuracy of treatment delivery [102].

In addition to the CBCT technology of acquiring volumetric images with soft-tissue structure definition, advances in image reconstruction and registration software permit rapid assessment of variation between the verification images and the reference planning images. Therefore, it is now feasible to scan a patient in the treatment position and implement an on-line couch correction to reposition the isocenter moments before treatment delivery. Such on-line corrections allow maximal geometric accuracy on a daily basis during a course of treatment.

Bladder variation: population, individualized & adaptive RT strategies

Measurement of bladder variation

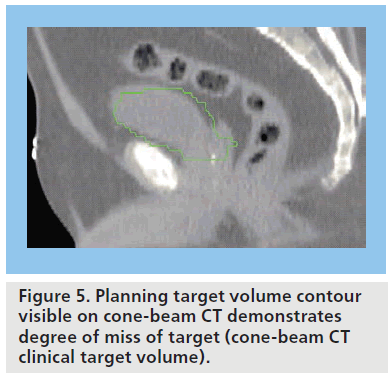

The bladder is a highly deformable organ subject to many factors influencing filling, including baseline hydration, oral fluid intake, renal function, concomitant medication, time since last void, bladder inflammation and obstruction. It is also a mobile structure within the pelvis and its position is influenced by surrounded structures such as the rectum [16]. A number of studies have demonstrated size, shape and positional changes using repeat diagnostic CT scans at regular intervals, typically weekly, during the course of RT [17–25]. The documented interfractional bladder variation is a challenge to accurate RT delivery and has necessitated a large isotropic (symmetric) safety margin of 1.5–2 cm to be added to the clinical target volume (CTV) to create the planning target volume (PTV). For any one individual, on a given day of treatment, this safety margin may be overgenerous and result in a large volume of normal tissue being irradiated. The studies have also demonstrated that a margin of this magnitude is inadequate for some fractions, with up to 89% of treatments delivered with a degree of ‘missing’ of the target (Figure 5) [21]. A drawback to assessing bladder variation on weekly diagnostic CT scans is the separation in time and place from treatment delivery; however, more recent studies using CBCT reveal similar variation [26–28].

Adjusting for patient positioning errors: isocenter shift

With the availability of CBCT it is now feasible to scan the patient, assess the patient position and implement a couch correction to reposition the isocenter moments before treatment delivery. One study demonstrated that without the ability to optimally shift the treatment isocenter, an isotropic margin of 3 cm was required to ensure the bladder CTV was covered on all subsequent images, but with CBCT-guided isocenter intervention an isotropic margin of 1.6 cm was adequate [24]. The average shift required in this study for the considerable reduction in safety margin was 0.7 cm and its direction was random.

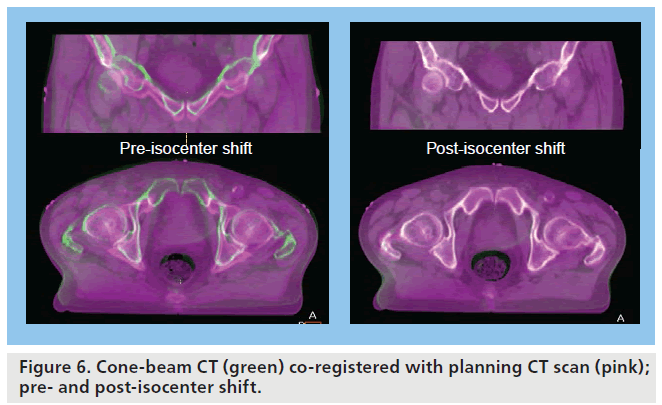

A CBCT-guided isocenter shift allows for reduction in patient set-up error in addition to reducing error owing to displacement of a consistent volume within the pelvis (Figure 6), for example, due to changes in rectal filling, as it allows a correction in three planes (Figure 4). On its own, an isocenter shift is not able to fully correct for internal motion due to changes in shape and volume of the target. Strategies to account for this are discussed below.

Adjusting for bladder volume changes: anisotropic margins

The observed population variation in size and shape of the bladder over time with filling is consistently greater in certain directions. Studies have documented that the greatest variations with bladder filling are in the cranial and anterior directions with minimal variation in the lateral and caudal directions [21–23,25,27]. These studies have led to development of population-based anisotropic CTV to PTV margins, greatest in the directions of most variation to account for the differential bladder motion with filling. Regular CBCT soft-tissue verification permits maximal benefit from implementation of anisotropic margins, by ensuring the population-based anisotropic margins remain valid for any individual patient throughout a course of treatment.

Individualization of treatment

As the bladder is an organ subject to such large day-to-day changes in size and shape between treatment fractions (interfraction variation), strategies to address the consequent uncertainty are required to improve RT delivery. There is the potential to reduce the margin required around the target if the volume variation can be reduced. For example, one study demonstrated that if the bladder volume could be maintained to within 150% of the volume observed on the initial planning scan then isotropic margins could be safely reduced from 1.5 to 1 cm [29]. Predictive factors would be useful to assess an individual at the treatment planning stage, to try to identify a group of patients for whom a smaller margin would be adequate. However, studies have so far failed to identify a reliable predictive factor. For example, patient age, pretreatment urinary toxicity score, post-voiding bladder volume at planning, increase in bladder volume over 30 min and tumor position within the bladder were assessed and not found to be predictive pretreatment factors [27]. The option of bladder catheterization to stabilize the bladder volume during a course of treatment would be a simple measure requiring minimal technology to implement; however, it has a number of drawbacks including patient discomfort and increased risk of urinary tract infection.

Rather than trying to predict and account for all potential target motion at the treatment planning stage, the availability of CBCT has led to the development of individualized adaptive RT strategies aimed at maintaining target coverage while reducing the amount of normal tissue irradiated.

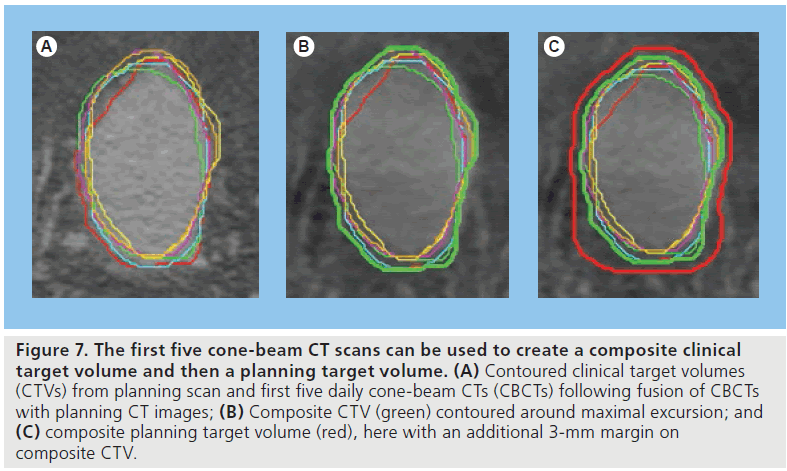

Composite volume technique

The composite volume technique was first described as a strategy for improving prostate RT treatment delivery [30] but has since been investigated in bladder RT [31]. In this study, 21 patients receiving RT for bladder cancer were treated using a 2-cm isotropic margin around the target for the first 2 weeks. Daily CBCT scans from the first 5 days were assessed at the end of the week. After fusion with the planning CT scan, the target was contoured on each scan and then maximal excursion of the target on all of these scans was used to define an adaptive volume to which a 1-cm (i.e., smaller) isotropic margin was added to create the adaptive PTV (Figure 7). Implementation of this new adaptive plan from the third week of treatment was associated with maintenance of target coverage on subsequent imaging despite an average 40% reduction in the PTV. The target in this study was a partial bladder volume around the tumor but the technique also lends itself to whole-bladder treatment planning. CBCT is important both in defining the adaptive volume and in ensuring validity of the composite volume on a regular, but not necessarily daily, basis during the treatment course.

Figure 7.The first five cone-beam CT scans can be used to create a composite clinical target volume and then a planning target volume. (A) Contoured clinical target volumes (CTVs) from planning scan and first five daily cone-beam CTs (CBCTs) following fusion of CBCTs with planning CT images; (B) Composite CTV (green) contoured around maximal excursion; and (C) composite planning target volume (red), here with an additional 3-mm margin on composite CTV.

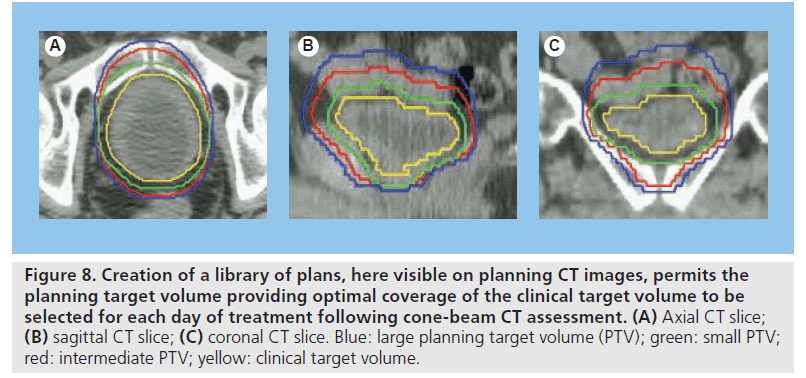

Figure 8.Creation of a library of plans, here visible on planning CT images, permits the planning target volume providing optimal coverage of the clinical target volume to be selected for each day of treatment following cone-beam CT assessment. (A) Axial CT slice; (B) sagittal CT slice; (C) coronal CT slice. Blue: large planning target volume (PTV); green: small PTV; red: intermediate PTV; yellow: clinical target volume.

‘Plan of the day’ selection

Given the degree of interfraction variation observed in bladder RT patients and the unpredictable nature of these variations, the availability of more than one plan at treatment delivery for best fit ‘plan of the day’ selection appears attractive. As plan of the day implies, daily imaging with CBCT is required for implementation of this adaptive strategy to permit appropriate soft-tissue-based plan selection (Figure 8). Published studies have varied approaches to creating a library of plans with differing degrees of individualization. An early study developed a library of three plans by varying the margin added in the superior direction to the CTV (0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 cm) [32]. Plan of the day selection in this cohort of 20 patients revealed target coverage could be maintained with a mean reduction in the PTV of 31 cm3 compared with the standard plan (1.5-cm superior margin). With the reduction in treatment volume superior to the target volume, this suggests potential for reduced irradiation of small bowel with this strategy. Interobserver concordance in the plan of the day selection was 70% in this study [32].

The margins applied around the target to create the various PTVs used for the library of plans can be population-based. An example of one of the adaptive strategies recently published was based on a library of small, intermediate and large plans with the CTV expanded using population-based margin data needed to encompass 50, 70 and 90% of the population [33]. However, further individualization can be considered in development of the library of plans either by using patient-specific information at the treatment planning stage or early on in the treatment course.

Individual interfraction variation

Similar to the composite volume approach, information from daily CBCT acquired during the first week of treatment can be used to develop a patient-specific library of plans for implementation later on in the treatment course. Two groups, who have recently published on this approach, have used the composite volume strategy to create one of the selection volumes [33,34]. One of these studies demonstrated that implementation of CBCT image-guided plan of the day selection improved target coverage with a significant mean reduction in the volume of irradiated normal tissue compared with the conventional approach [34]. Similarly, the other study also modeled adequate target coverage with reduction in volume of tissue irradiated to a high dose [33].

Adaptive-predictive organ localization

For bladder RT planning, our standard practice is to perform a single snap-shot CT scan after the patient has voided. By carrying out an additional interval CT scan, for example, half an hour later, time-dependant bladder filling information can be gained for each patient at the treatment planning stage. The observed volumetric changes of the bladder can be used as a model of the anticipated bladder variation for each individual. The advantage of creating a library of patient-specific plans prior to the start of a course of RT is that it can be implemented from the first day of treatment [35] rather than later in the treatment course, such as on day 8 [34] . Although CBCT images are not required for the development of the individualized plans, on-line CBCT imaging prior to each fraction remains essential for implementation of plan of the day selection.

As plan development does not rely on acquisition of CBCT early on in the treatment course, this technique lends itself well to hypofractionated RT with fewer overall treatments. Arguably, with a small number of larger fractions, image guidance and geometric accuracy with each treatment become even more important. The adaptive-predictive organ localization (A-POLO) methodology, with creation of patient-specific small, medium and large plans, has been modeled in 15 patients receiving hypofractionated bladder RT with one fraction each week for 5–6 weeks [27]. The results revealed that 24% of fractions would have benefited from improved target coverage by selection of the large plan over the standard or intermediate plan and 54% of fractions could have maintained target coverage with selection of the small plan rather than the standard plan, with a reduction in irradiation of surrounding normal tissue. Overall, 78% of the hypofractionated treatments would have benefited from the A-POLO plan of the day approach. In this study, the interobserver concordance rate in plan selection was 76%, consistent with earlier reports [32]. Studies of A-POLO in clinical practice are underway in our center and initial results from the first 14 patients receiving hypofractionated RT demonstrate an inter-observer plan selection concordance rate of 92%, and maintenance of adequate target coverage with a mean reduction in PTV of 42% compared with a conventional approach [36].

Tumor boost & fiducial markers

Partial bladder treatment & reduced high-dose volume

Conventional RT aims to deliver 64 Gy in 32 fractions to the whole bladder. It has been postulated that the development of bladder cancer is associated with a mucosal field change within the bladder and treatment should therefore include all bladder mucosa. However, the need to treat the whole bladder rather than the tumor alone has not been clearly established and this belief is questioned by the successful use of interstitial RT, which delivers a high, localized dose to the tumor only [37]. Data, including those of a randomized controlled trial in prostate cancer [38], have shown that shielding normal tissue can reduce side effects and possibly allow dose escalation.

There is little available data on the relative tolerance of the whole versus part of the bladder to radiation. It is widely accepted that the radiation tolerance of a whole bladder for development of a contracted scarred bladder known as the TD5/5 (5% risk at 5 years) is approximately 65 Gy, but there is suggestion that if part of the bladder is irradiated, the TD5/5 may be as high as 75–80 Gy [13,39], although these estimates may be flawed as bladder motion is not taken into account [40]. Our own experience of twophase RT treatment to the bladder (52 Gy to whole bladder followed by a 12-Gy tumor boost) showed a 50% reduction in severe late toxicity (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group grade 3 and 4 complication rates: 41 vs 22%; p = 0.034) compared with patients receiving conventional whole-bladder treatment to the same total dose (64 Gy) [41].

Partial bladder irradiation allows the full dose to be delivered to the tumor while the healthy bladder is, to varying degrees, spared [42]. A RT planning study at our hospital (Royal Marsden Hospital, Surrey, UK) has shown a 50% reduction in the volume of bladder treated above 60 Gy when only part of the bladder received the full dose of 64 Gy [43]. In addition to reducing the volume of bladder receiving a high dose, it is also possible to reduce volumes of small bowel and rectum receiving a high dose with anticipated reductions in toxicity [44].

The problems currently associated with partial bladder irradiation are:

• Difficulty visualizing the bladder tumor at planning CT scan due to previous transurethral resection of bladder tumor or shrinkage of radiologically visible tumor following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This difficulty can be reduced by availability of an accurate bladder map drawn by the urologist at the time of initial transurethral resection of bladder tumor;

• Bladder variability during treatment causing geographical miss of the high-dose volume (resulting in under treatment of target volume and over treatment of nearby structures that receive the dose instead).

Thus, bladder RT could benefit greatly from better demarcation of tumor position at the time of planning and also at the time of treatment to ensure target coverage. If treatment accuracy is improved, the size of safety margins applied could be reduced, with a corresponding reduction in the volume of nearby normal tissues irradiated.

MRI virtual cystoscopy

Studies are underway to investigate the use of MRI virtual cystoscopy in helping delineate the site of bladder tumor. Both MRI images and bladder maps based upon virtual cystoscopic findings can be used to determine the tumor site and, consequently, may allow better definition of the area to receive a tumor boost. However, this is only potentially useful at the planning stage of RT treatment and cannot be used during treatment to verify the bladder or tumor position.

Fiducial markers

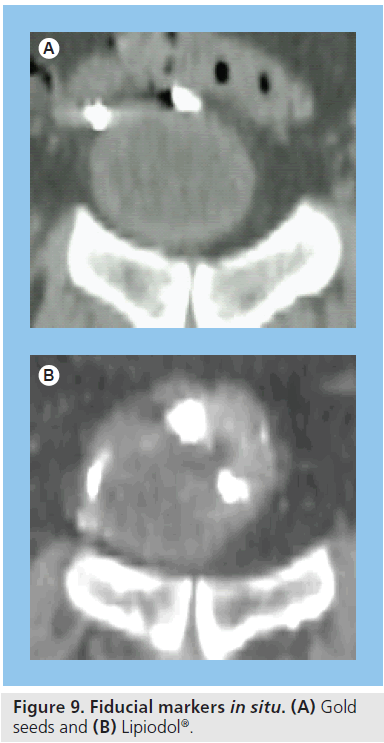

For all of its advantages, the quality of CBCT does not allow good definition of the extent of the gross tumor within the bladder, which is difficult to distinguish even on diagnosticquality CT scans. Implanted fiducial markers have previously been investigated in many other types of cancer as surrogate markers of tumor position. Radio-opaque gold seeds [45] or titanium clips [46] are the most widely used form of fiducial marker and their insertion into a target organ allows easy identification of tumor position in 2D or 3D imaging. These markers can be inserted into bladder mucosa via rigid cystoscopy to provide a surrogate marker of the extent of bladder tumor (Figure 9).

The markers can be used at treatment planning to assist the clinician in determining the tumor site to be encompassed in the treatment field. This is particularly important if a higher dose is to be delivered to a bladder tumor. In addition, these markers can be identified at the time of treatment delivery to allow improved accuracy. CBCT images taken immediately before treatment allow comparison with the planning scan so that the couch can subsequently be moved immediately before treatment to ensure the high-dose target volume is treated accurately and that the low-dose volume is adequately spared.

Lipiodol® (Guerbet) is a liquid contrast medium used mainly for lymphography and hysterosalpingography. It has also been used as a fiducial marker for tumor localization in lung and prostate patients and, more recently, for tumor demarcation in bladder patients for image-guided RT (Figure 9). Lipiodol can be injected into the bladder wall via a flexible cystoscope, which allows access to all parts of the bladder (compared with a rigid cystoscope) and is better suited to poor performance status patients who are unsuitable for the general anesthetic necessary for rigid cystoscopy. Lipiodol use combined with CBCT scanning has been demonstrated to be a feasible method for monitoring bladder tumor position changes during treatment [47,48].

It has been demonstrated that the tumor-laden bladder wall is less mobile than the unaffected part of the bladder [25] and that changes in tumor volume may be less pronounced than the volume changes seen in the bladder as a whole. It may also be the case that as the tumor regresses during the course of RT, the bladder wall becomes more compliant. The use of the combination of CBCT and fiducial markers makes it possible to observe movement of the tumor as well as of the entire bladder and to adapt treatment as necessary.

Alternative fiducial marker systems that do not utilize CBCT are in development with the aim of achieving real-time tumor tracking during treatment delivery, such as Calyspo® radiofrequency transponders for prostate cancer [49]. Tracking during treatment may be associated with additional benefit although further studies are required.

Pitfalls & problems

Limits to margin reduction with CBCT

When considering the possible margin reductions that image guidance may allow, it is important to remember that target-volume delineation variability remains an important limiting source of error. Studies have documented that contouring variations of pelvic organs are larger on CBCT compared with diagnostic CT images [50]. In addition, to allow for a degree of intrafraction bladder motion and filling, a small margin such as 0.3 cm [27] will still be required after an on-line match, immediately prior to treatment.

Image quality & artifact

All CBCT scans are inherently more prone to artifact than conventional radiographs because the images are reconstructed from many separate detector measurements. Typical artifacts seen are: streaking, shading, rings or distortion. CT artifact can arise from patient-related factors such as presence of metallic materials or movement, owing to the scanner or due to the method of image reconstruction employed. In comparison with diagnostic CT images, there is a compromise in achievable image quality when working with CBCT. The cone beam with the EPID detection system causes an increased scatter artifact, although scatter correction methods have been developed to deal with this issue. Softtissue contrast is better in kV CBCT scans owing to the prevalence of photoelectric absorption, but these interactions are also responsible for the presence of artifact from metallic objects within the patient. Conversely, MV CBCT scans do not show such good soft-tissue definition as those with kV CBCT, but are less prone to artifact due to metallic objects (or any other high-electrondensity object) owing to the predominance of Compton scatter as the attenuation mechanism at the higher-beam energies.

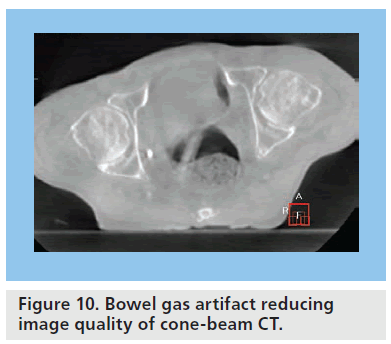

In the pelvis, causes of artifacts subject to more day-to-day variation include motion artifact from peristalsis and artifact due to bowel gas. Pockets of bowel gas within the bowel and rectum occur frequently and can significantly compromise CBCT image quality, making interpretation difficult on any given day (Figure 10) [51].

CBCT imaging radiation dose

There are also concerns that the increased radiation dose from the CBCT scans in addition to the prescribed therapeutic radiation could prove detrimental to the patient. The typical CBCT scan delivers a further 15 mSv of radiation. This represents a small percentage increase in overall radiation exposure to the patients and a recent study has demonstrated that the radiation exposure to the patient was reduced by using CBCT and adaptive strategies (due to smaller irradiated volume) in comparison to conventional RT [52].

Resource considerations

There is undoubtedly a cost implication for many hospitals, not just as a capital outlay for new equipment, but also its associated software. Furthermore, the time taken to deliver imageguided and/or adaptive RT is longer than for standard RT. The extended treatment time slots required to provide this treatment unit are likely to result in a decrease in patient throughput on the treatment unit.

In addition, the staff need to be educated to use the new equipment. In our center, we have a number of senior radiographer staff trained to assess a bladder CBCT image and compare it to the reference planning CT scan. They are capable of performing any necessary treatment couch movement and are able to choose an optimal plan of the day. Confident and timely decision making after CBCT acquisition is paramount for maximal benefit as any undue delay may allow for further patient movement and/or bladder filling. This advanced competency requires specific training and clinician support, particularly in the early stages of implementation.

There are also additional cost implications depending on the adaptive strategy used for each patient. Additional clinician time is required for creating a composite volume, as the planning requires analysis and contouring of multiple CTVs on the CBCTs acquired. Creation of a library of plans for plan of the day selection is usually less demanding on clinician time, but requires additional physics time for the generation of multiple plans for each patient. Having multiple plans available for a patient also requires strong governance mechanisms to ensure that the appropriate/correct treatment plan is selected each day.

Future perspective

Dose escalation

Introduction of advanced RT techniques has led to improved clinical outcomes in other tumor sites, for example, with tumor dose escalation in prostate cancer [53] and conformal avoidance of critical structures in head and neck cancer [54]. Clinical trials of the use of CBCT image-guided and adaptive RT are required to assess the potential clinical benefit to be gained from improved accuracy and individualization of treatment delivery. Adequate target coverage combined with reductions in the PTV and/or reduction in the volume of normal tissue treated has now been demonstrated in a number of studies using CBCT in bladder RT [24,31–34,36]. This raises the question of whether isotoxic doseescalation studies are now feasible. The dose– response curve observed for transitional cell carcinoma estimates an a:b ratio of 10–13 Gy [55]. This implies that dose escalation will result in improved outcome using standard 1.8–2 Gy per fraction. However, dose escalation with the availability of image guidance should be pursued cautiously as conventional RT techniques have most likely allowed some geographical miss or accidental sparing of the normal bladder tissue with its associated reduction in toxicity. By targeting the bladder more precisely, there is a possibility that bladder toxicity is increased even before the dose is escalated, purely for the reason that the bladder is fully included in the target volume that receives its prescribed dose.

Integration of CBCT with other RT techniques & systemic therapies

In addition to image-guided adaptive strategies discussed above, additional questions about the RT technique remain to try to gain maximum therapeutic benefit. For example, it may be that there is a patient subgroup that only requires a tumor volume alone to be treated rather than any whole-bladder treatment, but another patient subgroup may benefit for the inclusion of pelvic lymph nodes using highly conformal intensity-modulated RT in addition to treatment of the bladder. Another question is whether dose escalation is best approached with standard fractionation or whether a concomitant boost technique (delivering higher than the standard 2 Gy per fraction to the boost region) [56] is preferable. Now that there is published evidence of improved outcomes from bladder RT with the addition of concomitant chemotherapy [6] and concomitant administration of radiosensitizers [57], the gain from these systemic therapies may be additive with potential gains from CBCT image guidance.

Developmental strategies: immediate replanning & dose-guided RT

Ultimately, it may be possible to use the information from the daily CBCT images to monitor the accuracy of treatment by provision of information on the delivered dose distribution. With technical advances in deformable registration and optimization algorithms, immediate replanning based on this information may become practical in the not too distant future [58].

Conclusion

The increasing availability of CBCT within the RT delivery room has expanded our horizon. There is opportunity to take a quantum leap in the delivery of RT to bladder cancer to make this treatment one suitable for the 21st century. The development of innovative correction and adaptive protocols to correct for bladder and patient motion will allow us to deliver truly personalized RT treatments; these promise real gains in terms of minimizing treatment toxicity for similar cure rates or allowing isotoxic treatments for improved cure rates via treatment intensification (either by RT dose escalation and/or concomitant therapies). These improved treatments may allow RT to challenge the supremacy of radical surgery as the local treatment of choice for this patient group.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

*of interest

* of considerable interest

References

- Cookson MS: The surgical management of muscle invasive bladder cancer: a contemporary review. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 15, 10–18 (2005).

- Hall CM, Dinney CP: Radical cystectomy for stage T3b bladder cancer. Semin. Urol. Oncol. 14(2), 73–80 (1996).

- Smith JA Jr, Crawford ED, Paradelo JC et al.: Treatment of advanced bladder cancer with combined preoperative irradiation and radical cystectomy versus radical cystectomy alone: a Phase III intergroup study. J. Urol. 157(3), 805–807 (1997).

- Stimson CJ, Chang SS, Barocas DA et al.: Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. J. Urol. 184(4), 1296–1300 (2010).

- Hautmann RE, Simon J: Ileal neobladder and local recurrence of bladder cancer: patterns of failure and impact on function in men. J. Urol. 162(6), 1963–1966 (1999).

- James ND: Results of a Phase III randomized trial of synchronous chemoradiotherapy (CRT) compared to radiotherapy (RT) alone in muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (BC2001 CRUK/01/004). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(3), S2–S3 (2010). & Best evidence that concomitant chemo-radiotherapy improves results over radiotherapy alone and that chemo-radiotherapy can be tolerated by the majority of patients.

- Huddart RA, Hall E, Lewis R, Birtle A: Life and death of spare (selective bladder preservation against radical excision): reflections on why the spare trial closed. BJU Int. 106(6), 753–755 (2010).

- Rodel C, Grabenbauer GG, Kuhn R et al.: Combined-modality treatment and selective organ preservation in invasive bladder cancer: long-term results. J. Clin. Oncol. 20(14), 3061–3071 (2002).

- Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R et al.: Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 19(3), 666–675 (2001).

- Kotwal S, Choudhury A, Johnston C, Paul AB, Whelan P, Kiltie AE: Similar treatment outcomes for radical cystectomy and radical radiotherapy in invasive bladder cancer treated at a United Kingdom specialist treatment center. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 70(2), 456–463 (2008). & Good comparison of outcomes from surgery and radiotherapy showing similar results.

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Meta-analysis Collaboration: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 361(9373), 1927–1934 (2003).

- Choudhury A, Swindell R, Logue JP et al.: Phase II study of conformal hypofractionated radiotherapy with concurrent gemcitabine in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 29(6), 733–738 (2011).

- Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A et al.: Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 21(1), 109–122 (1991).

- Korreman S, Rasch C, Mcnair H et al.: The European Society of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology-European Institute of Radiotherapy (ESTRO-EIR) report on 3D CT-based in-room image guidance systems: a practical and technical review and guide. Radiother. Oncol. 94(2), 129–144 (2010)

- Xing L, Chang J, Orton CG: Point/counterpoint. Kilovoltage imaging is more suitable than megavoltage imaging for guiding radiation therapy. Med. Phys. 34(12), 4563–4566 (2007).

- Lotz HT, Remeijer P, Van Herk M et al.: A model to predict bladder shapes from changes in bladder and rectal filling. Med. Phys. 31(6), 1415–1423 (2004).

- Sur RK, Clinkard J, Jones WG et al.: Changes in target volume during radiotherapy treatment of invasive bladder carcinoma. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 5(1), 30–33 (1993).

- Turner SL, Swindell R, Bowl N et al.: Bladder movement during radiation therapy for bladder cancer: implications for treatment planning. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 39(2), 355–360 (1997). & Classic article illustrating variation in bladder shape and position throughout a course of treatment.

- Harris SJ, Buchanan RB: An audit and evaluation of bladder movements during radical radiotherapy. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 10(4), 262–264 (1998).

- Pos FJ, Koedooder K, Hulshof MC, Van Tienhoven G, González González D: Influence of bladder and rectal volume on spatial variability of a bladder tumor during radical radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 55(3), 835–841 (2003).

- Muren LP, Smaaland R, Dahl O: Organ motion, set-up variation and treatment margins in radical radiotherapy of urinary bladder cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 69(3), 291–304 (2003).

- Meijer GJ, Rasch C, Remeijer P, Lebesque JV: Three-dimensional analysis of delineation errors, setup errors, and organ motion during radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 55(5), 1277–1287 (2003).

- Fokdal L, Honore H, Hoyer M, Meldgaard P, Fode K, Von Der Maase H: Impact of changes in bladder and rectal filling volume on organ motion and dose distribution of the bladder in radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 59(2), 436–444 (2004).

- Redpath AT, Muren LP: CT-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for bladder cancer: isocentre shifts, margins and their impact on target dose. Radiother. Oncol. 81(3), 276–283 (2006).

- Lotz HT, Pos FJ, Hulshof MC et al.: Tumor motion and deformation during external radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 64(5), 1551–1558 (2006).

- Henry AM, Stratford J, Mccarthy C et al.: X-ray volume imaging in bladder radiotherapy verification. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 64(4), 1174–1178 (2006).

- Lalondrelle S, Huddart R, Warren-Oseni K et al.: Adaptive-predictive organ localization using cone-beam computed tomography for improved accuracy in external beam radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 79(3), 705–712 (2011). & Planning study documenting potential advantages of adaptive radiotherapy using an optimal ‘plan of the day’.

- Yee D, Parliament M, Rathee S, Ghosh S, Ko L, Murray B: Cone beam CT imaging analysis of interfractional variations in bladder volume and position during radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 76(4), 1045–1053 (2010).

- Mangar SA, Miller NR, Khoo VS et al.: Evaluating inter-fractional changes in volume and position during bladder radiotherapy and the effect of volume limitation as a method of reducing the internal margin of the planning target volume. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 20(9), 698–704 (2008).

- Yan D, Lockman D, Brabbins D, Tyburski L, Martinez A: An off-line strategy for constructing a patient-specific planning target volume in adaptive treatment process for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 48(1), 289–302 (2000).

- Pos FJ, Hulshof M, Lebesque J et al.: Adaptive radiotherapy for invasive bladder cancer: a feasibility study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 64(3), 862–868 (2006). & First adaptive bladder radiotherapy study demonstrating reduction in planning target volume with an adaptive approach.

- Burridge N, Amer A, Marchant T et al.: Online adaptive radiotherapy of the bladder: small bowel irradiated-volume reduction. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 66(3), 892–897 (2006).

- Vestergaard A, Sondergaard J, Petersen JB, Hoyer M, Muren LP: A comparison of three different adaptive strategies in image-guided radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Acta Oncol. 49(7), 1069–1076 (2010).

- Foroudi F, Wong J, Kron T et al.: Online adaptive radiotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of a pilot study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. DOI: 10.1016/j. ijrobp.2010.06.061 (2010) (Epub ahead of print).

- Mangar SA, Scurr E, Huddart RA et al.: Assessing intra-fractional bladder motion using cine-MRI as initial methodology for predictive organ localization (POLO) in radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 85(2), 207–214 (2007).

- Mcdonald F, Lalondrelle S, Taylor H et al.: Delivering adaptive radiotherapy in the clinic: Preliminary experiences from the APPLY study [Adaptive-Predictive Planning for Hypo-Fractionated Bladder RT]. Radiother. Oncol. 96 (S1), 177 (2010).

- Lybeert ML, Ribot JG, De Neve W, Goor C, Crommelin MA: Carcinoma of the urinary bladder: long-term results of interstitial radiotherapy. Bull. Cancer Radiother. 81(1), 33–40 (1994).

- Dearnaley DP, Khoo VS, Norman AR et al.: Comparison of radiation side-effects of conformal and conventional radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 353(9149), 267–272 (1999).

- Marks LB, Carroll PR, Dugan TC, Anscher MS: The response of the urinary bladder, urethra, and ureter to radiation and chemotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 31(5), 1257–1280 (1995).

- Viswanathan AN, Yorke ED, Marks LB, Eifel PJ, Shipley WU: Radiation dose-volume effects of the urinary bladder. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 76(3 Suppl.), S116–S122 (2010).

- Mangar SA, Foo K, Norman A et al.: Evaluating the effect of reducing the high-dose volume on the toxicity of radiotherapy in the treatment of bladder cancer. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 18(6), 466–473 (2006). & Pilot study suggesting benefit from reduced high-dose volume method of bladder radiotherapy.

- Cowan RA, Mcbain CA, Ryder WD et al.: Radiotherapy for muscle-invasive carcinoma of the bladder: results of a randomized trial comparing conventional whole bladder with dose-escalated partial bladder radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 59(1), 197–207 (2004). & First randomized trial of reduced-volume bladder radiotherapy showing no detriment to patient outcome.

- Huddart R, Staffurth J: What is the most effective way of reducing normal tissue toxicity in radical radiotherapy treatment of muscle invasive bladder cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 64(S1), 305 (2002)

- Mcdonald F, Rogers S, Hall E, James N, Huddart R: Defining bowel dose-volume constraints for bladder radiotherapy: using data from patients entered into a Phase III randomised trial. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 7(2), 163–164 (2009).

- Mangar S, Thompson A, Miles E, Huddart R, Horwich A, Khoo V: A feasibility study of using gold seeds as fiducial markers for bladder localization during radical radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 80(952), 279–283 (2007). & First description of use of fiducial markers in bladder radiotherapy.

- Hulshof MC, Van Andel G, Bel A, Gangel P, Van De Kamer JB: Intravesical markers for delineation of target volume during external focal irradiation of bladder carcinomas. Radiother. Oncol. 84(1), 49–51 (2007).

- Pos F, Bex A, Dees-Ribbers HM, Betgen A, Van Herk M, Remeijer P: Lipiodol injection for target volume delineation and image guidance during radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 93(2), 364–367 (2009). & Describes the use of injectable fiducial agent Lipiodol® and advantages for bladder radiotherapy.

- Chai X, Van Herk M, Van De Kamer JB et al.: Behavior of Lipiodol markers during image guided radiotherapy of bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 77(1), 309–314 (2010).

- Kupelian P, Willoughby T, Mahadevan A et al.: Multi-institutional clinical experience with the Calypso System in localization and continuous, real-time monitoring of the prostate gland during external radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 67(4), 1088–1098 (2007).

- Weiss E, Wu J, Sleeman W et al.: Clinical evaluation of soft tissue organ boundary visualization on cone-beam computed tomographic imaging. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 78(3), 929–936 (2010).

- Smitsmans MH, Pos FJ, De Bois J et al.: The influence of a dietary protocol on cone beam CT-guided radiotherapy for prostate cancer patients. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 71(4), 1279–1286 (2008).

- Kron T, Wong J, Rolfo A, Pham D, Cramb J, Foroudi F: Adaptive radiotherapy for bladder cancer reduces integral dose despite daily volumetric imaging. Radiother. Oncol. 97(3), 485–487 (2010).

- Dearnaley DP, Sydes MR, Graham JD et al.: Escalated-dose versus standard-dose conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer: first results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 8(6), 475–487 (2007).

- Nutting C: Dose-escalation chemo-IMRT improves locoregional control rates in organ preservation treatment of locally advanced laryngeal and hypopharengeal cancers. Radiother. Oncol. 90(Suppl. 2), S11 (2009).

- Majewski W, Maciejewski B, Majewski S, Suwinski R, Miszczyk L, Tarnawski R: Clinical radiobiology of stage T2–T3 bladder cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 60(1), 60–70 (2004).

- Muren LP, Redpath AT, Mclaren D et al.: A concomitant tumour boost in bladder irradiation: patient suitability and the potential of intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 80(1), 98–105 (2006).

- Hoskin PJ, Rojas AM, Bentzen SM, Saunders MI: Radiotherapy with concurrent carbogen and nicotinamide in bladder carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 28(33), 4912–4918 (2010).

- Cheung J, Aubry JF, Yom SS, Gottschalk AR, Celi JC, Pouliot J: Dose recalculation and the Dose-Guided Radiation Therapy (DGRT) process using megavoltage cone-beam CT. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 74(2), 583-592 (2009).