Research Article - International Journal of Clinical Rheumatology (2018) Volume 13, Issue 6

Impact of obesity on rheumatoid arthritis: Relation with disease activity, joint damage, functional impairment and response to therapy

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gharbia OM

Department of Rehabilitation and Rheumatology

Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Egypt

E-mail: sherineabdelrahman@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background and Aim of Work: The impact of Body Mass Index (BMI) on outcomes of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is uncertain. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of obesity on Egyptian patients with RA.

Methods: Medical records of 146 RA patients were reviewed. Patients were categorized into normalweight, overweight and obese groups based on BMI. The clinical and laboratory indices of RA activity, the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and the radiographic damage score were compared among the groups at baseline, 8, 16 and 24 months.

Results: DAS28 and HAQ score were matched at baseline but improved in the 3 groups thereafter, however, differences among the groups become significant only at 24-month. At the 24-month, DAS28 was significantly better in normal-weight (2.1 ± 1.0) and in overweight groups (2.2 ± 0.8) compared to obese group (2.7 ± 1.0) (normal-weight vs obese p=0.003 and overweight vs obese p= 0.006). At the 24-month, HAQ score was significantly better in normal-weight (0.78 ± 0.6) and in overweight groups (0.82 ± 0.5) compared to obese group (1.09 ± 0.7) (normal-weight vs obese p= 0.16 and overweight vs obese p= 0.041). The radiological Sharp-van der Heijde Score along the study period was lower in obese than in overweight or normal-weight patients, albeit the differences in the radiological score were insignificant among the groups.

Conclusion: Obese patients were shown to have a poorer response rate to treatment in all outcome measures in comparison to the overweight and the normal-weight RA patients. Future research work is required to investigate whether weight reduction can decrease non-remission rate among the obese RA patients.

Keywords

obesity, body mass index, rheumatoid arthritis, disease activity

Abbreviations

Anti-CCP: Anti-cyclic Citrullinated Peptide Autoantibodies; BMI: Body Mass Index; CRP: C-reactive Protein; DAS: Disease Activity Score; DMARDs: Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; IL: interleukin; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; RF: Rheumatoid Factor; SJC: Swollen Joint Counts; TJC: Tender Joint Counts; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; VAS-Pain: Visual Analogue Scale For Pain

Introduction

Despite the significant therapeutic advances of the medical treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), a considerable sector of the patients show inadequate response to treatments and, therefore, are at increased risk of incident medical complications, functional disability and lowered health-related quality of life [1- 3]. Accordingly, it is worthy to recognize factors that predict the outcome of the disease.

Obesity is a prevalent co-morbidity in patients with RA. It had been reported that from 18% [4] to 31% [5] of the RA patients are obese. However, in these two studies, >60% of RA patients were overweight or obese. The impact of obesity on outcomes of RA is uncertain. It was hypothesized that higher Body Mass Index (BMI) is associated with more active and severe disease in RA, based on the inflammatory nature of the two conditions. Obesity is implicated in the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, and thus, obese patients exhibit more active and severe disease. White adipose tissue is a dynamic organ that secretes several bioactive molecules including Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, cytokines and adipokines. Most of these molecules had pro-inflammatory activities responsible for the chronic low-grade systemic inflammatory status. These pro-inflammatory molecules are increased in RA, and form a link between obesity and RA [6].

However, studies investigated the effect of obesity on RA had revealed a conflicting results. Numerous studies have observed that obese or overweight RA patients have an inadequate response to treatment with poor outcomes including lower probability to achieve RA disease remission and more functional impairment [7-10]. Some studies reported that obesity increases disease activity [11,12]. Conversely, an higher BMI was found to be associated with more favorable radiographic outcome [9,13]. Moreover, it is suggested that obesity may slowdown the radiographic progression in the early phases of RA [14,15]. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of obesity on patients with RA.

Patients and methods

Study population

In this study the medical records of RA patients in the Outpatient Clinics of the Physical Medicine, Rehabilitation and Rheumatology Department, Mansoura University Hospital were reviewed in the period from June 2015 to July 2017. All patients had fulfilled the 2010 EULAR/ACR criteria [16].

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any autoimmune rheumatic disease other than RA, evidence of malignancy, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and concurrent infection were excluded from the study. Pregnant women, patients younger than 19 years or older than 65 years were also excluded from the study. In addition, patients on biological therapy were excluded from the study to eliminate its effect on the course of the disease, unifying the treatment strategy for all the patients included.

Data collection

Every RA patient with the following data complete at the baseline, 8, 16 and 24 month evaluations was included:

• BMI.

• Clinical outcome measures including the Visual Analogue Scale for pain (VAS-pain) and the 28 tender (TJC) and Swollen Joint Counts (SJC).

• Laboratory outcome measures including the C-Reactive Protein (CRP); Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR). In addition the Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and the Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide autoantibodies (Anti- CCP) positivity were determined at baseline.

• Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28 [17] and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) [18].

• The Radiographic score (Sharp-van der Heijde Score) [19]. The radiographic score was obtained at baseline and at 24-months.

After review of medical records, these data were found complete in 146 RA patients records and were included and analyzed. According to their baseline BMI, the RA patients were allocated in three groups:

• Normal-weight RA group - patients with BMI <25 kg/m2.

• Overweight RA group - patients with BMI ranges from 25 to 29.9 kg/m2.

• Obese RA group - patients with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were processed and analyzed with SPSS program (version 20.0). Variables with continuous data were examined for the normality of distribution. Variables including continuous data and categorical data were compared by the means of Student’s t test while and chi square test respectively. Statistically significance was set at p value lower than 0.05.

Results

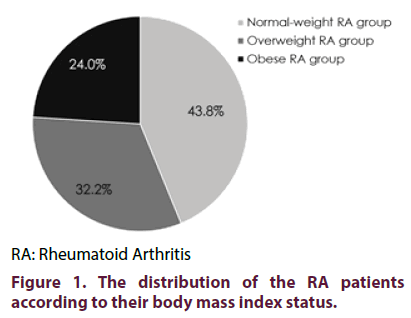

Out of the 146 patients included in the present study, 64 (43.8%) had normal BMI, 47 (32.2%) were overweight while 35 (24.0%) were obese (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, the three groups were matched regarding the age, sex and duration of the disease. Also, drug intake as well as the presence of RF and anti-CCP antibodies did not differ significantly among the groups. The BMI and the outcome measures were recorded at the baseline and every 8 months over 2-years. None of the patients had shown any significant change in the BMI.

| Normal- BMI RA patients | Overweight RA patients | Obese RA patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 64 | 47 | 35 | |

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 43.1 ± 13.5 | 41.9 ± 13.8 | 42.2 ± 11.2 | 0.885 |

| Females (n, %) | 44, 68.8% | 29, 61.7% | 26, 74.3% | 0.472 |

| Duration of RA (mean ± SD) | 11.4 ± 5.4 | 10.2 ± 5.1 | 10.5 ± 5.2 | 0.46 |

| Methotrexate use (n, %) | 52, 81.3% | 39, 83.0% | 29, 82.9% | 0.966 |

| Leflunomide use (n, %) | 24, 37.5% | 16, 34.0% | 11, 31.4% | 0.822 |

| Hydroxychloroquine use (n, %) | 47, 73.4% | 33, 70.2% | 26, 74.3% | 0.902 |

| Sulfasalazine use (n, %) 15 | 4, 6.3% | 2, 4.3% | 1, 2.9 | 0.735 |

| Rheumatoid factor +ve (n, %) | 51, 79.7% | 34, 72.3% | 28, 80% | 0.602 |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide +ve (n, %) | 39, 60.0% | 29, 61.7% | 23, 65.7% | 0.891 |

Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the RA patients.

Changes in the TJC, SJC and VAS-pain scores over the 24-months

At baseline, the 3 groups were matched regarding the TJC, SJC and VAS-pain. At the 8- and at 16-months, the TJC, SJC and the VAS-pain were decreased in the 3 groups, albeit, the differences among the groups were insignificant but differences become significant at 24-months (p=0.018, 0.019 and 0.030 respectively). Post hoc test showed that, at the 24-months, the TJC, SJC and the VAS-pain were significantly higher in the obese group than normalweight (p=0.007, p=0.011 and p=0.015 respectively) and then the overweight group (p=0.035, p=0.038 and p=0.036, respectively) meanwhile differences of TJC, SJC and the VAS-pain between the normalweight group and overweight group at the 24-months were insignificant (Table 2).

| Normal-BMI RA patients | Overweight RA patients | Obese RA patients | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tender joint count | ||||

| Baseline | 16.5 ± 5.6 | 17.1 ± 4.7 | 17.3 ± 5.2 | 0.724 |

| 8-months | 10.4 ± 5.3 | 11.3 ± 5.5 | 12.1 ± 5.0 | 0.299 |

| 16-months | 8.6 ± 4.2 | 8.5 ± 4.2 | 10.1 ± 4.4 | 0.176 |

| 24-months | 7.5 ± 3.0 | 7.7 ± 3.5 | 9.5 ± 4.1 | 0.018 |

| Swollen joint count | ||||

| Baseline | 16.4 ± 5.8 | 16.9 ± 5.4 | 16.7 ± 5.4 | 0.894 |

| 8-months | 9.8 ± 4.0 | 10.6 ± 4.3 | 10.3 ± 4.5 | 0.604 |

| 16-months | 7.3 ± 2.9 | 7.8 ± 3.3 | 8.4 ± 4.4 | 0.312 |

| 24-months | 6.0 ± 3.2 | 6.3 ± 2.9 | 8.0 ± 4.4 | 0.019 |

| Pain (mm) | ||||

| Baseline | 55.2 ± 10.7 | 55.3 ± 10.9 | 56.6 ± 10.6 | 0.808 |

| 8-months | 37.4 ± 10.9 | 38.6 ± 11.5 | 41.5 ± 12.9 | 0.245 |

| 16-months | 27.5 ± 10.9 | 28.0 ± 11.2 | 31.1 ± 12.8 | 0.308 |

| 24-months | 20.9 ± 10.8 | 21.5 ± 10.3 | 26.9 ± 12.6 | 0.03 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm) | ||||

| Baseline | 79.4 ± 22.1 | 79.0 ± 18.9 | 77.9 ± 23.3 | 0.946 |

| 8-months | 62.6 ± 19.7 | 62.1 ± 18.3 | 67.9 ± 18.6 | 0.326 |

| 16-months | 41.2 ± 17.5 | 41.8 ± 18.8 | 47.6 ± 17.2 | 0.207 |

| 24-months | 34.3 ± 16.6 | 34.6 ± 17.8 | 43.6 ± 17.3 | 0.024 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | ||||

| Baseline | 33.0 ± 13.3 | 31.8 ± 11.4 | 34.1 ± 14.4 | 0.727 |

| 8-months | 26.9 ± 9.9 | 27.7 ± 8.2 | 30.4 ± 13.4 | 0.271 |

| 16-months | 22.6 ± 10.5 | 23.7 ± 8.7 | 26.9 ± 13.0 | 0.157 |

| 24-months | 19.7 ± 9.7 | 20.5 ± 8.4 | 25.6 ± 12.4 | 0.017 |

Table 2. Comparison of the clinical and laboratory indices among the normal-weight, overweight and obese RA patients during the follow up period.

Changes in the ESR and CRP serum levels over the 24-months

The changes of the laboratory outcomes followed the same pattern as the clinical outcomes. The ESR and the CRP serum levels were matched among the 3 groups at baseline and at the 8- and 16-months evaluations but differences become significant at 24-months (p=0.024 and 0.017 respectievly). Post hoc test showed that, at the 24-months, obese group has significantly higher ESR and lower CRP levels than the normal-weight group (p=0.021 and p=0.010, respectively) and then overweight group (p=0.045 and p=0.029 respectively) but differences between the normal-weight and overweight groups were insignificant (Table 2).

BMI categories and the changes in the DAS28 and HAQ scores over the 24-months

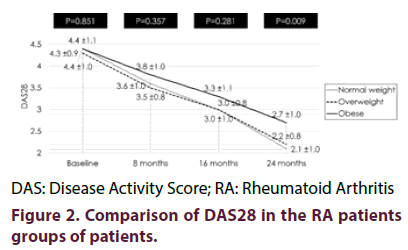

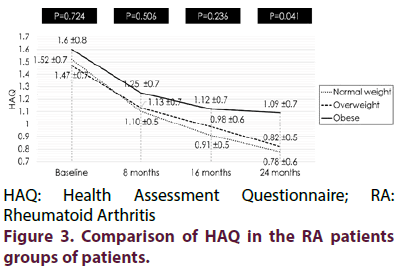

No significant difference regarding the DAS28 and HAQ scores among the three groups at the baseline, at 8-months and at 16-months meanwhile were significant at 24-months (p=0.009 and 0.047). Post hoc test showed that, at the 24-months, the normal-weight RA patients and the overweight RA patients had a significantly lower DAS28 (p=0.003 and p=0.006, respectively) (Figure 2) and a significantly lower HAQ score than obese group (p=0.016 and p=0.041 respectively) (Figure 3).

HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis

Figure 3. Comparison of HAQ in the RA patients groups of patients.

BMI categories and the radiographic progression over the 24-months

The differences in radiographic scores were insignificant among the groups at baseline, 8-, 16- nor 24-months. However, at 24-months, the obese group has lower radiological score than in the overweight or normal-weight patients (45.3 ±12.7, 48.9 ±11.1 and 49.3 ±9.8, %, respectively).

Discussion

The present study shows that obesity is associated with a significant decrease in the improvement in clinical/laboratory outcome measures as well as the DAS28 and HAQ in RA patients compared with overweight/normal weight. It is also indicated that obesity is inversely associated with radiographic progression but is not significantly significant.

The results of the present study showed that 56.2% of the consecutive RA patients enrolled in this study were overweight or obese (32.2% and 24.0% respectively). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among the RA patients varied greatly among the studies. Younis and Al-Bustany showed that 80.0% of RA patients were overweight and obese (33.3% and 46.7%) [20]. Crowson et al. reported that 40.3% of RA patients were obese [21]. Giles et al. reported that 33% of females and 36% of males with RA were obese [22]. In Armstrong et al. study, the reported prevalence of obesity in RA patients was 31% [5]. These differences could be attributed to potential geographical factors, lifestyle factors, eating patterns and variations of exercise performance.

The results of the current study had shown that, for every outcome measure, a higher BMI status (obese > overweight > normal-weight) was associated with the worse clinical and laboratory records, with worse DAS28 scores and with worse functional impairment. However, the outcome measures were significantly better in the normal-weight and in the overweight groups compared to the obese group. In agreement to the findings of this study, Levitsky et al. reported that obesity was the strongest independent factor for prediction of non-remission among the RA patients despite the initiation of treat-to-target approach [23]. Also, study of Younis and Al-Bustany showed a positive association between obesity and disease activity since patients with higher BMI had higher DAS28 and also higher clinical disease activity index [20]. These findings are also consistent with those of Vidal et al. [9] who reported that the DAS28 appeared to be higher in obese than in normal-weight RA patients. In Jawaheer et al. study, a total of 5161 patients with RA were enrolled and the data analysis had shown that BMI (continuous or categorical) is positively associated with DAS28 [24].

Ajeganova et al. enrolled 1596 patients with early RA, 12.9% were obese at inclusion. They observed that obesity early and during follow up was strongly related to higher RA activity, fewer RA patients in the sustained remission rate and more pain. Furthermore, that study revealed that HAQ score was significantly higher in obese group in comparison to the normalweight group, a finding that is consistent with the results of the current study [25].

It is important to mention that no significant associations were found between BMI and RF anti- CCP in RA patients in the current study. The findings of the study of Younis and Al-Bustany [20] is in agreement with the results of this study. However, two previous studies observed that obesity is significantly associated with increased likelihood for development of anti-CCP-negative RA [26,27], meanwhile Lu et al. found that risks of anti-CCP-positive and anti-CCPnegative RA were increased in overweight and obese females, especially those with early disease [28].

The association between obesity and nonremission had also been reported by several previous studies. In the study of Gremese et al., obesity represented a risk factor for a poorer remission rates in RA patients treated with three different anti-TNF-α treatments. In that study, obese RA patients on infliximab showed even poorer outcome measures than the other two anti-TNF-α treatments, the etanercept and adalimumab that are not adjusted for body weight [29]. In addition, Klaasen et al. initiated infliximab treatment in 89 RA patients who had active disease. The BMI was obtained prior to the start of treatment and the dose of the infliximab was adjusted to the body weight for every patient. They reported a poorer 4-months response to infliximab in obese patients, despite that the infliximab dosage is adjusted to body weight [30]. The findings of that study support the notion that obesity is associated with lower response rate to treatment in RA patients.

There is considerable evidence that confirm the relationship between inflammation and obesity. Free fatty acids, which are increased in the obese as a result of the excess amounts of adipose tissue, can activate macrophage cells [31]. The excess production of adipocytokines, produced mainly by adipose tissues, create a loop of chronic inflammation due to continuous activation of macrophages [32]. Besides the adiponectin (inversely associated with BMI) and leptin (positively associated with BMI) which play a central role in RA progression, the white adipose tissues produce TNF-α and IL-6. These findings reveal the link between the adipose tissue and the chronic inflammatory state [23].

The radiological score from the baseline to the 24-months follow up points was less frequent in the obese group than in the overweight or normal-weight groups, but these differences were insignificant. The same finding was reported by Levitsky et al. [23]. Interestingly, Westhoff et al. found that RA group with normal-weight already showed significantly higher joint damage score at study entry than obese group and at 3-years follow up, their radiographic score was 2-fold as high as that of the obese group [14]. Daïen and Sellam found that obesity is potentially linked with a lower probability of increasing in van der Heijde-Sharp score at the weeks 52 and 104 despite aggressive treatment even after adjustment of likely confounders [33]. Ina addition, these radiological results were proved in a study of MRI-evidenced progression in erosions score in two-years follow up period time [13].

The current study had shown that obese RA patients had consistently worse disease clinical and laboratory outcomes, worse disease activity and worse functional impairment. Obesity is a modifiable risk factor. An area worthy of future investigation is weather a personalized treatment plan that include weight reduction of obese RA patients may lead to better outcome in obese RA patients who showed inadequate response despite treatment.

Conclusion

Obese patients were shown to have a poorer response rate to treatment in all outcome measures in comparison to the overweight and the normalweight RA patients. Future research can assess weight reduction with relevance to poorer response rate to treatment in all outcome measures in obese patients with RA.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board/Mansoura Faculty of Medicine/Mansoura University (R/ 17.06.78; approval date, 20th July 2017).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Please contact author for data requests.

Authors’ contributions

Gharbia OM participated in study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision. El- Bahnasawy AS participated in study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision. Okasha AE participated in study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision. Abd El-Karim SA participated in study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of manuscript and critical revision.

Funding

No funding support was received for this study.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

References

- Neovius M, Simard JF, Klareskog L et al. Sick leave and disability pension before and after initiation of antirheumatic therapies in clinical practice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70(8), 1407–1414 (2011).

- Eriksson JK, Neovius M, Bratt J et al. Biological vs. conventional combination treatment and work loss in early rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. JAMA. Intern. Med. 173(15), 1407–1414 (2013).

- Cutolo M, Kitas GD, van Riel PL. Burden of disease in treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: Going beyond the joint. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 43(4), 479–488 (2014).

- Naranjo A, Sokka T, Descalzo MA et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 10(2), R30 (2008).

- Armstrong DJ, McCausland EM, Quinn AD et al. Obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 45(6), 782–783 (2006).

- Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, KoutedakisY et al. Obesity in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 50(3), 450–462 (2011).

- Ellerby N, Mattey DL, Packham J et al. Obesity and comorbidity are independently associated with a failure to achieve remission in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73, e74 (2014).

- Sandberg ME, Bengtsson C, Källberg H et al. Overweight decreases the chance of achieving good response and low disease activity in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73(11), 2029–2033 (2014).

- Vidal C, Barnetche T, Morel J et al. Association of body mass index categories with disease activity and radiographic joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rheumatol. 42(12), 2261–2269 (2015).

- Liu Y, Hazlewood GS, Kaplan GG et al. Impact of obesity on remission and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis. Care. Res. 69(2), 157–165 (2017).

- García-Poma A, Segami MI, Mora CS et al. Obesity is independently associated with impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 26(11), 1831–1835 (2007).

- Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Panoulas VF et al. Underweight and obese states both associate with worse disease activity and physical function in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 28(4), 439–445 (2009).

- Baker JF, Ostergaard M, George M et al. Greater body mass independently predicts less radiographic progression on X-ray and MRI over 1-2 years. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73(11), 1923–1938 (2014).

- Westhoff G, Rau R, Zink A. Radiographic joint damage in early rheumatoid arthritis is highly dependent on body mass index. Arthritis. Rheum. 56(11), 3575–3827 (2007).

- van der Helm-van Mil AH, van der Kooij SM, Allaart CF et al. A high body mass index has a protective effect on the amount of joint destruction in small joints in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 67(6), 769–774 (2008).

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69(9), 1580–1588 (2010).

- van Riel PL. The development of the Disease Activity Score (DAS) and the disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28). Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 32(5 Suppl 85), S65–S74 (2014).

- Bruce B, Fries J. The stanford health assessment questionnaire: A review of its history, issues, progress, and documentation. J. Rheumatol. 30(1), 167–178 (2003).

- Van der Heijde D, Dankert T, Nieman F et al. Reliability and sensitivity to change of a simplification of the Sharp/van der Heijde radiological assessment in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford). 38(10), 941–947 (1999).

- Younis KR, Al-Bustany DA. Prevalence of obesity in rheumatoid arthritis and its association with disease activity and latex positivity in a sample of patients in Erbil. Zanko. J. Med. Sci. 21(2), 1726–1735 (2017).

- Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Davis JM et al. Contribution of obesity to the rise in incidence of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis. Care. Res. 65(1), 71–77 (2013).

- Giles J, Ling S, Ferruci L et al. Abnormal body composition phenotypes in older rheumatoid arthritis patients: Association with disease characteristics and pharmacotherapies. Arthritis. Care. Res. 59(6), 807–815 (2008).

- Levitsky A, Brismar K, Hafström I et al. Obesity is a strong predictor of worse clinical outcomes and treatment responses in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the SWEFOT trial. RMD. Open. 3(2), e000458 (2017).

- Jawaheer D, Olsen J, Lahiff M et al. Gender, body mass index and rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: Results from the QUEST-RA Study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 28(4), 454–461 (2010).

- Ajeganova S, Andersson ML, Hafström I et al. Association of obesity with worse disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis as well as with comorbidities: A long-term follow up from disease onset. Arthritis. Care. Res. 65(1), 78–87 (2013).

- Pedersen M, Jacobsen S, Klarlund M et al. Environmental risk factors differ between rheumatoid arthritis with and without auto-antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 8(4), R133 (2006).

- Wesley A, Bengtsson C, Elkan AC et al. Epidemiological investigation of rheumatoid arthritis study group. Association between body mass index and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population-based case-control study. Arthritis. Care. Res. 65(1), 107–112 (2013).

- Lu B, Hiraki L, Sparks JA et al. Being overweight or obese and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis among women: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73(11), 1914–1922 (2014).

- Gremese E, Carletto A, Padovan M et al. Obesity and reduction of the response rate to anti-tumor necrosis factor α in rheumatoid arthritis: an approach to a personalized medicine. Arthritis. Care. Res. 65(1), 94–100 (2013).

- Klaasen R, Wijbrandts CA, Gerlag DM et al. Body mass index and clinical response to infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis. Rheum. 63(2), 359–364 (2011).

- Boden G. Obesity and free fatty acids. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 37(3), 635–646 (2008).

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6(10), 772–783 (2006).

- Daïen CI, Sellam J. Obesity and inflammatory arthritis: impact on occurrence, disease characteristics and therapeutic response. RMD. Open. 1(1), e000012 (2015).