Case Report - International Journal of Clinical Rheumatology (2019) Volume 14, Issue 1

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis - case report of two patients and review of literature

- Corresponding Author:

- Eugenia Schwarzkopf

Sloan Kettering Institute

1275 York Avenue

New York, NY 10065, USA

E-mail: eugenia.schwarzkopf28@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO) is an autoinflammatory skeletal disease characterized by unifocal or multifocal nonbacterial inflammatory bone lesions in the metaphysis of long bones. Common sites of CRMO are tibia, pelvis, proximal femur, clavicle, calcaneum and vertebrae. However, unifocal presentation or presentation in adults, atypical locations, and absence of recurrence have also been reported. Methods and Findings: We describe two cases of female patients with unifocal presentation of nonbacterial inflammatory bone lesions in the upper and lower extremity. Furthermore, a review of literature is presented. Conclusion: Although CRMO is seen primarily in children and adolescents, and usually occurs in a multifocal pattern, our cases illustrate that this disease can arise in adult patients and in a single location. The diagnosis of CRMO should be made in a multi-disciplinary approach amongst orthopedic surgeons, radiologists and pathologists.

Keywords

chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis • chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis • nonbacterial inflammatory bone lesions • CRMO

Introduction

Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis (CRMO) is an autoinflammatory skeletal disease characterized by unifocal or multifocal nonbacterial inflammatory bone lesions in the metaphysis of long bones [1]. CRMO is a very rare disease, but can result in substantial longterm morbidity [2]. It was first described in 1972 by Giedon et al. who called it “chronic symmetrical osteomyelitis” [3], and later renamed CRMO by Gustavson et al. [4] and Probst et al. in 1978 [5]. The cause of this disease remains unclear, and the true prevalence is unknown [6]. CRMO primarily occurs in children or adolescents, young girls are affected more often [7]. The clinical manifestation of CRMO is highly variable; it is characterized by multiple remissions and recurrences and may be accompanied by fevers or other extraskeletal conditions including psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis, Crohn’s disease, severe acne, Sweet syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis and Takayasu’s arteritis [2,8-10]. Common sites of CRMO are tibia, pelvis, proximal femur, clavicle, calcaneum and vertebrae [2]. However, unifocal presentation or presentation in adults, atypical locations, and absence of recurrence have also been reported [11,12]. Differential diagnoses include osteomyelitis, primary bone tumors, lymphoma or Langerhans cell histiocytosis [2].

In our report, we present two cases of CRMO in a single location. Further, we discuss etiological, clinical, radiological and histopathological features to facilitate diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Finally, we present a review of literature.

Case description

Case 1

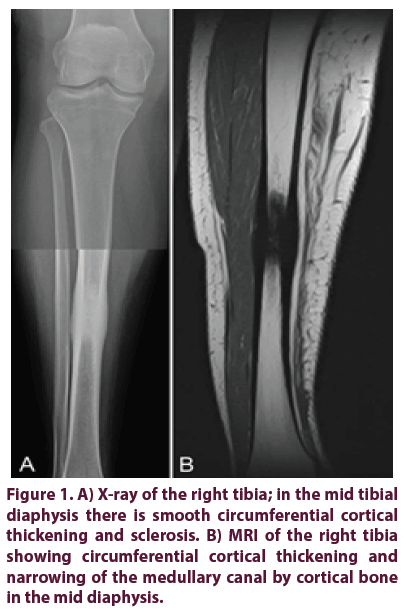

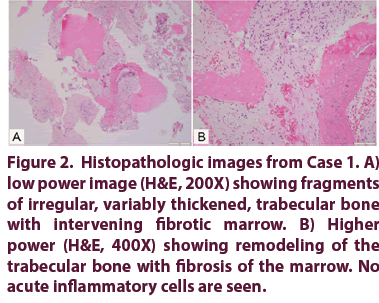

A 34-year-old woman presented at our institution with severe pain in the right tibia after experiencing a motor vehicle accident with no direct trauma to her right lower leg nine months prior to her presentation. She had a history of morbid obesity and hypertension without an autoimmune condition. The patient was pregnant at the time of the accident and had only mild clinical symptoms in the tibia, so no imaging was done at initial presentation. Following a premature birth, the patient experienced swelling and increasing discomfort in the right leg. The clinical examination showed tenderness to palpation over the mid shaft of the tibia without palpable soft tissue mass. Radiographs and MRI showed a lesion in the right mid shaft tibia with significant cortical and periosteal reaction raising the possibility of a healing fracture with underlying pathologic process (Figures 1A and 1B). A whole-body bone scan and radiographs of the chest revealed no further signs of disease. An open biopsy of the lesion was performed, showing sclerotic lesions of the bone with non-specific fibrotic marrow findings without evidence of malignancy (Figure 2A) and negative microbiology cultures. The patient was treated conservatively with a walking boot. However, the pain in the right lower leg persisted.

Another MRI four months later showed no improvement but stable cortical thickening of the tibial diaphysis. The presumptive diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis was made, and the patient was treated with right tibia intramedullary reaming six months after her initial biopsy. Pathology of the reamed fragments showed woven and laminar bone with no evidence of a tumor or osteomyelitis, and microbiology cultures were negative again. The patient had significant pain relief after the procedure for ten months before returning with a dull ache in her right anterior medial tibia. Radiographs again showed stable sclerosis and cortical thickening. Due to progressive pain, another open biopsy was performed three years after the initial biopsy (Figure 2B). Pathology showed fragments of cortical and trabecular bone with focal mild remodeling and no inflammation.

Figure 2: Histopathologic images from Case 1. A) low power image (H&E, 200X) showing fragments of irregular, variably thickened, trabecular bone with intervening fibrotic marrow. B) Higher power (H&E, 400X) showing remodeling of the trabecular bone with fibrosis of the marrow. No acute inflammatory cells are seen.

Ultimately, a multidisciplinary consensus amongst orthopedic surgeons, radiologists and pathologists proposed the diagnosis of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. The patient underwent an intramedullary nail (IMN) to reinforce the tibia which improved the pain. Periodically, she experienced an insidious onset of pain and swelling in the right lower extremity without fever, chills or any other constitutional symptoms; during these episodes, she limited her activities, walked with a cane and took pain medication such as non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

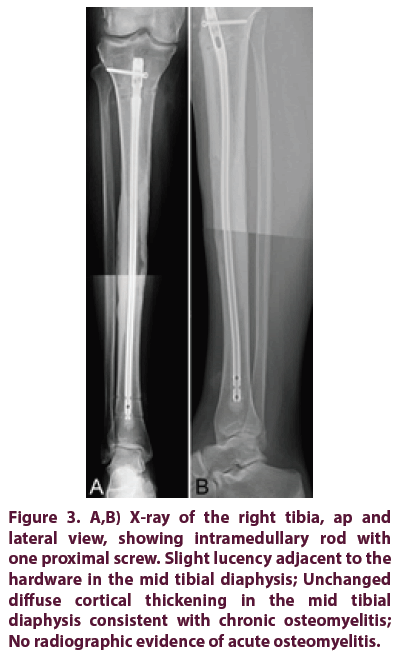

Six years after the implantation of the IMN, the patient presented in our outpatient clinic due to increasing pain in the right lower leg. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) were 26 mm/hr and 1.19 mg/dl, respectively. Clinical examination revealed tenderness and swelling over the right tibia, and the concern of surgery related osteomyelitis was raised. Therefore, the patient underwent IMN removal and insertion of a new gentamicin-impregnated cement-coated IMN (Figures 3A and 3B). Intraoperatively, loose friable tissue was found without frank pus. Histology showed bone remodeling and marrow fibrosis and the diagnosis of CRMO was made. At the last follow-up visit, there was no sign of recurrent infection or hardware failure. The patient returned to all of her normal activities, has full range of motion and is weight-bearing without assistance.

Figure 3: A,B) X-ray of the right tibia, ap and lateral view, showing intramedullary rod with one proximal screw. Slight lucency adjacent to the hardware in the mid tibial diaphysis; Unchanged diffuse cortical thickening in the mid tibial diaphysis consistent with chronic osteomyelitis; No radiographic evidence of acute osteomyelitis.

Case 2

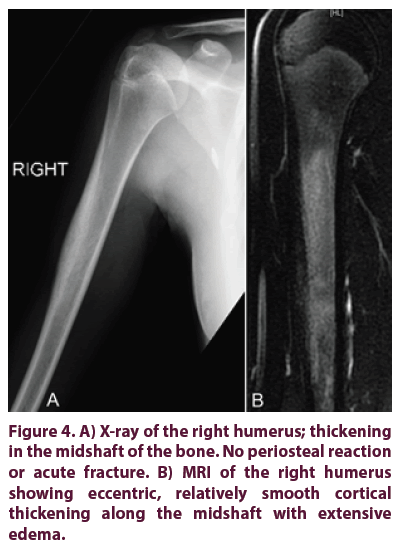

A 14-year-old girl presented at our outpatient clinic with a history of pain in her right arm for two years. Episodes of pain sometimes lasted from days to months; however, the pain would be relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Trauma, fevers, chills, nausea, weight loss, and change in bowel or bladder habits were denied. There was a family history of autoimmune-disease: the patient’s brother and father were diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and Grave’s disease, respectively. Clinical examination showed free range of motion in the upper extremity, no obvious lesion or palpable soft tissue mass over the right arm. All inflammatory indexes including CRP, ESR and white-blood cell count were within normal limits. X-ray and MRI of the right upper extremity demonstrated abnormal marrow infiltration of the humeral diaphysis with endosteal and periosteal reaction (Figures 4A and 4B). Radiographs of the chest and a whole-body bone scan revealed no further lesions. Differential diagnosis included tumoral infiltration and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis.

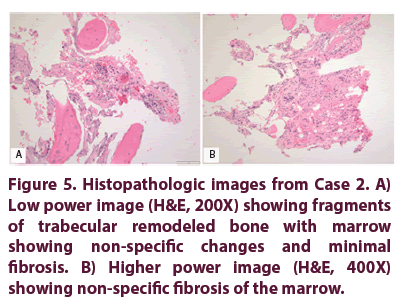

An open biopsy was performed, revealing a fatty bone marrow with foci of increased vascularity, histiocytes and minimal chronic inflammatory cells (Figures 5A and 5B); cultures have been negative. Initially, the patient was asymptomatic without pain medication. However, a year and a half after the biopsy, the patient presented at our outpatient clinic with onset of right humerus pain again, radiating down to her elbow and wrist. Trauma or changes in activities of daily living were denied. On clinical examination, the patient had full range of motion, no pain or tenderness in her right upper extremity. Radiographs of the right humerus showed a hyper sclerotic region of the bone, consistent with the biopsy tract. Blood work was negative. After a two weeks course of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, the pain subsided.

One year later, the patient presented at our institution with similar symptoms. MRI revealed diffuse marrow edema, otherwise no other bony abnormalities were found. One year later, the patient presented with another episode of rightsided upper extremity pain. Again, clinical, radiographic and laboratory findings were unspecific. Different treatment options were discussed with the patient, including conservative therapy or placement of IMN to reinforce the bone. In the absence of any symptoms that prevent her from activities of daily living, the patient agreed to have regular follow-up visits with the Orthopaedic Service and Rheumatology in order to explore the autoimmune nature of this disease.

Discussion

Etiology

The pathogenesis and etiology of this condition is currently unknown [13,14]. Some reports suggest an infectious origin; suspected organisms include Staphyloccocus aureus, Mycoplasma hominis, Propionibacterium acnes and Chlamydia [15-17]. However, larger studies could not support this result [6,18,19]; the infectious origin has now been ruled out as the underlying cause [7]. The association between CRMO, dermatologic disorders (psoriasis, palmo-plantar pustulosis), inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis) and its response to steroids led to the conclusion of an underlying autoimmune cause [6,20,21]. More recently, observation of this disease in siblings [22,23] and identification of a susceptibility locus at 18q21.3-22 [24] suggest a genetic cause.

Clinical features

CRMO is characterized by inflammatory, sterile bone lesions and a uniphasic or recurrent clinical course of pain exacerbations and remissions [25]. This disease is self-limiting, but unpredictable; it may or may not be accompanied by fever, weight loss or other systemic manifestations [6]. CRMO affects the metaphysis of long bones, most commonly the tibia, femur and clavicle. Typically, patients present with unspecific complaints including pain, tenderness, swelling or limited range of motion [6]. The lesions can be unifocal or multifocal, bilateral involvement is common [1,13]. The mean age at onset of symptoms is 10 years [26,27], but it has been reported in older patients up to the age of 55 years [16,19]. The mean time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of CRMO ranges from weeks to several years [26]. Due to erratic, vague symptoms, the onset of CRMO and duration of the symptoms is hard to assess.

Imaging

The findings at imaging studies are not pathognomonic; they can only be suggestive of CRMO [6]. On imaging, it can be difficult to distinguish between CRMO and bone neoplasms [28]. On plain radiographs, the appearance of CRMO can range between purely osteolytic, osteolytic with a sclerotic rim, mixed lytic and sclerotic, and purely sclerotic [6]. A smooth character of the periosteal bone can differentiate CRMO from a neoplastic process, whereas periosteal reaction in neoplastic changes is more spiculated [29]. For further evaluation, MRI can be used [6] to demonstrate transphyseal involvement, marrow edema, periostitis, soft-tissue inflammation, and nodular or annular juxtaphyseal contrast uptake [6,7]. Whole-body MRI can disclose a multifocal pattern or subclinical inflammatory lesions [7]. Radionuclide whole body bone scan can help to identify additional regions of involvement but is not helpful in differentiating CRMO from a neoplastic process [29].

Histopathological findings

The pathologic findings of CRMO are nonspecific [19]. The findings are usually reported descriptively rather than as a diagnosis. The changes observed include a spectrum from no significant changes to mild remodeling of the trabecular and/or cortical bone. The changes in the bone marrow include a spectrum from no significant changes to minimal fibrosis and inflammation [30]. A predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and osteoclastic bone resorption with or without multinucleated giant cells can be seen in the acute stages of CRMO. During progression of the disease, the predominant features are lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and increased osteoblast activity [6,19]. No overt inflammation or fibrosis was seen in either of the two presented cases.

Diagnostic strategy

Since there are no diagnostic criteria for CRMO, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion [12]. Patients often present with non-specific symptoms including pain, swelling or limited range of motion at one or more sites but there is a great variability in the number of affected sites, recurrence rates and prognosis. Falip et al. [7] proposed a diagnostic strategy to facilitate diagnosis and decision-making: If clinical and laboratory findings are non-conclusive but somewhat suggestive of CRMO, radiographic and MR imaging should be the next step; a whole-body MRI can identify multifocal and subclinical lesions. If imaging reveals multifocal lesions at typical sites, the patients should be treated for CRMO and followed up regularly. If the lesions are radiographically atypical, a biopsy should be performed. In our cases, the lesions were atypical and solitary; a biopsy was performed. to rule out infection or a neoplastic process.

Treatment

No antibiotic treatment has been reported to be effective for this condition [2]. Hendrich et al. proposed a therapeutic escalation regimen for the treatment of CRMO [31,32]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be utilized as firstline therapy. If disease activity is high at the time of diagnosis, addition of corticosteroids may be considered. If there is no response after three months, second-line treatment consisting of bisphosphonates and TNF-alpha inhibitors should be considered in complicated and severe forms; sulfasalazine and methotrexate can be used in the treatment of concomitant inflammatory bowel disease or skin involvement. The treatment goal is clinical remission; in the case of spinal involvement, complete radiological remission should be achieved to avoid vertebral fractures and gibbus formation [32]. Long-term follow-up is necessary [33].

Conclusion

In our report, clinical, laboratory, pathologic, and radiographic findings were not specific. Extensive evaluation led to the diagnosis of CRMO. Although this syndrome usually occurs with multifocal lesions in young patients, our cases illustrate that CRMO can occur in a single location at different ages. It is difficult to establish an accurate diagnosis in the absence of pathognomonic diagnostic features.

Review of literature

We present a comparison of demographics, pattern of lesions, symptoms, diagnostic methods, treatment options and response to treatment in CRMO patients is presented to facilitate decision making for diagnosis and treatment of CRMO (Table 1) [7,18,34-36].

| Paper | Ata et al. [34] | Falip et al. [7] | Girschik et al. [18] | Carr et al. [35] | Jurik et al. [36] |

| Demographics: | |||||

| No. of patients | 14 | 31 | 30 | 22 | 15 |

| Age at diagnosis (y)1 | 11.3 | 11 | 11 | 10.4 | 13.1 |

| Sex | 5 ♀, 9 ♂ | 22 ♀, 9 ♂ | 21 ♀, 9 ♂ | 14 ♀, 8 ♂ | 10 ♀, 5 ♂ |

| Follow-up (mo.)1 | 39 | 60 | 67.2 | 74.8 | 66 |

| Lesions: | |||||

| Anatomic sites | 1. Feet | 1. Femur | 1. Clavicle | 1. Tibia | 1. Clavicle |

| 2. Knees | 2. Spine | 2. Femur | 2. Pelvis | 2. Tibia | |

| 3. Hands | 3. Tibia | 3. Calcaneus | 3. Clavicle | 3.Femur | |

| Multifocal disease | 12 (86%) | 25 (81%) | 18 (58%) | 22 (100%) | 9 (60%) |

| No. of lesions (per patient)1 | 11.8 | 3.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| Symptoms: | |||||

| First symptoms | Pain, fever | Local pain, swelling | Pain, swelling, impairment of motion | Relapsing pain, malaise | Pain, swelling, malaise, fever |

| Duration of symptoms (mo.) before diagnosis1 | 8.3 | NA | 8 | 24 | 18 |

| Diagnosis: Laboratory1 | |||||

| Leukocytes/l | - | ↑ in 2 (6%) pat. | 8.6x109 | Normal in all pat. | Normal in all pat. |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.6 | ↑ in 9 (29%) pat. | 0.6 | na | na |

| ESR (mm/h) | 23 | ↑ in 15 (48%) pat. | 15 | 47 | ↑ in 12 (80%) pat. |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1288 | na | 1203 | ↑ in 1 (4%) pat. | ↑ in 1 (7%) pat. |

| Imaging modalities | X-ray, MRI, FDG-PET, DEXA | na X-ray, CT, MRI (standard + body) | X-ray, Bone scan, MRI, CT | X-ray, Bone scan | X-ray, Bone scan |

| Biopsy | 14 (100%) | 24 (77%) | 25 (83%) | 20 (91%) | 12 (80%) |

| Treatment: | |||||

| NSAIDs | + | + | + | + | + |

| Antibiotics | - | - | - | 4 | 6 |

| Surgery (other than biopsy) | 0 (0%) | 0 (%) | 1 (3%)3 | 1 (4%)5 | 7 (47%)7 |

| Response | |||||

| Remission | 10 (71%)2 | - | 30 (100%) | 18 (82%) | 15 (100%) |

| Relapse | - | - | 12 (40%) | - | - |

Table 1. Unifocal presentations of chronic multifocal osteomyelitis and review of the literature.

Funding

Research at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (#P30CA008748).

Conflict of Interest

The authors certify that they have no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. This work was performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

References

- Alberdi-Saugstrup M, Nielsen SM. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and tnf-αlfa inhibitors. Pediatr. Rheumatol. 11(Suppl 2), P324 (2013).

- Ract I, Storey J, Travers JY et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Diagn. Interv. Imaging. 96(3), 313-316 (2015).

- Giedion A, Holthusen W, Masel LF et al. Subacute and chronic "symmetrical" osteomyelitis. Annales. de. Radiologie. 15(3), 329-342 (1972).

- Gustavson KH, Wilbrand HF. Chronic symmetric osteomyelitis. Report of a case. Acta. Radiol. 15(5), 551-557 (1974).

- Probst FP, Bjorksten B, Gustavson KH. Radiological aspect of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Ann. Radiol. 21(2-3), 115-125 (1978).

- Khanna G, Sato TSP, Ferguson P. Imaging of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Radiographics: a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc 29(4), 1159-1177 (2009).

- Falip C, Alison M, Boutry N et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): a longitudinal case series review. Pediatr. Radiol. 43(3), 355-375 (2013).

- Barrani M, Massei F, Scaglione M et al. Unusual onset of a case of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Pediatr. Radiol. 13, 60 (2015).

- Dagan O, Barak Y, Metzker A. Pyoderma gangrenosum and sterile multifocal osteomyelitis preceding the appearance of Takayasu arteritis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 12(1), 39-42 (1995).

- Pelkonen P, Ryöppy S, Jääskeläinen J et al. Chronic osteomyelitislike disease with negative bacterial cultures. Am. J. Dis. Child. 142(11), 1167-1173 (1988).

- Figueiredo MP, Pato M, Amaral F. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: a case report with atypical presentation. J. Orthop. Case. Rep. 7(1), 75-78 (2017).

- Hong CW, Hsiao EC, Horvai AE et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis with an atypical presentation in an adult man. Skeletal. Radiol. 44(9), 1359-1364 (2015).

- Acikgoz G, Averill LW. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: Typical patterns of bone involvement in whole-body bone scintigraphy. Nucl. Med. Commun. 35(8), 797-807 (2014).

- Al Hajry M, Al Jumaah S, Almayouf SM. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: A first report from Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi. Med. 32(6), 611-614 (2012).

- Cyrlak D, Pais MJ. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Skeletal. Radiol. 15(1), 32-39 (1986).

- Marino C, McDonald E, Megna D et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in adult women. N Y State. J. Med. 92(8), 360-362 (1992).

- Kozlowski K, Anderson RJ, Hochberger O et al. Tumorous osteomyelitis. Pediatr. Radiol. 14(6), 404-406 (1984).

- Girschick HJ, Raab P, Surbaum S et al. Chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis in children. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64(2), 279-285 (2005).

- Bjorkstén B, Boquist L. Histopathological aspects of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. J. Bone. Joint. Surg. 62(3), 376-380 (1980).

- Laxer RM, Shore AD, Manson D et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and psoriasis-a report of a new association and review of related disorders. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 17(4), 260-270 (1988).

- Bousvaros A, Marcon M, Treem W et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis associated with chronic inflammatory bowel disease in children. Dig. Dis. Sci. 44(12), 2500-2507 (1999).

- Jansson A, Renner ED, Ramser J et al. Classification of non-bacterial osteitis: Retrospective study of clinical, immunological and genetic aspects in 89 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 46(1), 154-160 (2007).

- Majeed HA, Al-Tarawna M, El-Shanti H et al. The syndrome of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia. Report of a new family and a review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 160(12), 705-710 (2001).

- Golla A, Jansson A, Ramser J et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): Evidence for a susceptibility gene located on chromosome 18q21.3-18q22. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10(3), 217-221 (2002).

- Ferguson PJ, El-Shanti HI. Autoinflammatory bone disorders. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 19(5), 492-498 (2007).

- Catalano-Pons C, Comte A, Wipff J et al. Clinical outcome in children with chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 47(9), 1397-1399 (2008).

- Huber AM, Lam P-Y, Duffy CM et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: Clinical outcomes after more than five years of follow-up. J. Pediatr. 141(2), 198-203 (2002).

- Viejo-Fuertes D, Rossillon R, Mousny M et al. Primary chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis-a case-report. Joint. Bone. Spine: Revue du Rhumatisme. 72(1), 73-75 (2005).

- Bracamonte JD, Roberts CC. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis mimicking osteosarcoma. Radiol. Case. Rep. 1(2), 42-46 (2006).

- Wurm MC, Brecht I, Lell M et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in association with pyoderma gangraenosum. BMC. Oral. Health. 16(1), 85 (2016).

- Hedrich CM, Hahn G, Girschick HJ et al. A clinical and pathomechanistic profile of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis/chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and challenges facing the field. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 9(9), 845-854 (2013).

- Hedrich CM, Hofmann SR, Pablik J et al. Autoinflammatory bone disorders with special focus on chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online. J. 11(1), 47 (2013).

- Buckley G, Easty M, Compeyrot-Lacassagne S et al. Role of bone scan and MRI in the detection of bone inflammation in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74(Suppl 2), 1225.2-1225 (2015).

- Ata Y, Inaba Y, Choe H et al. Bone metabolism and inflammatory characteristics in 14 cases of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online. J. 15(1), 56 (2017).

- Carr AJ, Cole WG, Roberton DM et al. Chronic multifocal osteomyelitis. J. Bone. Joint. Surg. 75-B(4), 582-591 (1993).

- Jurik AG, Helmig O, Ternowitz T et al. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: A follow-up study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 8(1), 49-58 (1988).