Review Article - Clinical Practice (2019) Volume 16, Issue 4

"Explanation of how do individuals with multiple sclerosis cope with social isolation"

- Corresponding Author:

- Sorush Niknamian

Ph.D. in Cell and Molecular Biology,

CSci (Chartered Scientist), RSciTech

(Registered Science Technician), RSci

(Registered Scientist) ID: A0008833,

Science Council, United Kingdom

and Indiana Cancer Consortium (ICC)

certified.

Liberty University, United States of

America, Military Medicine, UK.K

E-mail: so.niknamian@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurological disease that can severely affect the psychosocial aspects of primary caregivers of individuals with MS (PCIMS). Objective: This study aimed to explore the process of social isolation among PCIMS in Kerman, Iran. Methods: This study was performed with grounded theory approach through a semi-structured interview with PCIMS (n=15), individuals with MS (n=13), and healthcare providers (n=5) who were selected through purposive and theoretical sampling in Kerman, Iran, during February 2017-April 2018. The data were analyzed through constant comparison method recommended by Corbin and Strauss. Results: Yield of this study was a theory in which "social isolation" was recognized as a core variable. "Lack of awareness and information", "Occupational Difficulties”, " Marital Difficulties, and " Endeavor to Reduce Restrictions" were the other extracted concepts that were related to the core variable which altogether contributed to its exploration. Conclusion: The results of this study showed that social isolation could endanger the well-being of PCIMS. This is the first study which shows to reduce the social isolation of PCIMS it is needed to address both the mutual needs and interests of the caregiver and the care-recipient. Therefore, occupational therapists are advised to design appropriate co-occupations based on the mutual needs and interests of the caregivers and the care-recipients to reduce the social isolation of these caregivers. For an in-depth examination, it is also suggested that studies be conducted discovering relationships between the concepts found in this theory.

Keywords

Multiple sclerosis, primary caregivers, social isolation, grounded theory, co-occupations

Introduction

MS is one of the most common debilitating neurological diseases [1]. Therefore, in performing some of their daily activities patients may over time need a caregiver. Usually, this role is assumed by a family member or a close friend, without receiving any payment, who is called primary caregiver [2]. Assuming the caregiving role for an ill person can lead to social isolation [3]. Social isolation can be defined as having restricted meaningful physical communication with others [4]. In general population studies of adults and older adults, individuals who have experienced social isolation were at higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease [5], cognitive deterioration [6], and mortality [7]; while vice versa, individuals who have more social communications are happier and healthier and have a longer life span [8]. Social isolation in primary caregivers of individuals with chronic diseases can lead to a caregiving burden and reduces their well-being [9]. Studies with the aim to describe the caregiving experience of PCIMS, have reported PCIMS being at risk of social isolation [10,11], but none of them had the main aim of in-depth exploration of the factors and the process of this phenomenon in PCIMS. Bogosian et al. in their study regarding exploration of the experience of the partners of individuals in the early stages of MS have pointed out that social isolation is present in PCIMS even when their care-recipient is in the early stages of MS, where still no tangible caregiving burden is imposed. They also emphasized the need for further research on identifying the determinants of social isolation factors in PCIMS [11]. Therefore, this study was designed to explore the process of social isolation of PCIMS and its influential factors in depth. The discovery of this process can help design further researches and theoretically-based interventions in this area, thereby reduce the caregiving burden and improve the health of the caregivers.

Boeije et al. believed that caregiving had a dynamic and dyadic nature, and to study caregiving experience it is better to regard both caregivers and care-recipients, as well as the manner of communication between them [12]. Bassi et al. also believed that PCIMS and their care-recipient can mutually influence each other’s behaviors and coping strategies [13]. Therefore, in this study, both partners were considered as interacting individuals, and effective factors and strategies of both partners which were used to explore the process of social isolation in PCIMS were investigated.

Material and Methods

In this study, grounded theory recommended by Corbin and Strauss [14] was used since caregiving is interactional, multidimensional, and context-bound phenomena. In such studies, grounded theory is suitable for creating an explanatory theory in such phenomena.

Setting and Participants

The present study was conducted in the MS Society at Samen Al Hojaj Hospital, Kerman, Iran during February 2017-April 2018. Inclusion criteria consisted of having experience of caring for MS patients, and willingness to participate in the study. Therefore, this study initiated by selecting caregivers of MS patients using purposive sampling. Then, to discover the relationships between the extracted concepts, theoretical sampling was conducted. To achieve theoretical saturation interviews were conducted with care-recipients and healthcare providers who were involved with these caregivers and care-recipients. Finally, 33 participants, including 15 PCIMS, 13 care-recipients, and 5 healthcare providers, from the MS community who had to deal with this caregivers and carerecipients participated in the study (TABLE 1 shows demographic characteristics of the participants).

| Characteristics of PCIMS | |

|---|---|

| Gender | 9 male, 6 female |

| Age (years) | Median: 40; range: 22-58 |

| Job | 8 employed, 2 retired, 5 home-maker |

| Marital status | 12 married, 2 single, 1 divorced |

| Education | 4 primary, 3 diploma,6 bachelors, masters |

| Length of caregiving (years) | Median: 6; range:1-15 |

| Relationship with the care-recipient | 2 mothers, 1 father, 2 daughters, 1 cousin, 5 husband, 3 wives, 1 sister |

| Characteristics of people with MS | |

| 10 female, 3 male | Gender |

| Median: 34; range: 21-50 | Age (years) |

| 4 employed, 2 student, 7 house keeper | Job |

| 9 married, 3 single, 1 divorced | Marital status |

| 2 primary, 3 diploma,2 bachelor student, 4 bachelor , 2 master | Education |

TABLE 1. Participants' demographics (N=33).

Data Collection

After obtaining an introductory letter from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, data were collected by principal investigator based on the interview guide and through semi-structured interviews in the MS Society. Interviews began with openended questions, with the participating PCIMS. For example: "What is your opinion about living with an MS patient?" Then, questions were gradually directed toward the research question. For example: "Have you faced difficulties in performing this role of caregiving? ». To extract the essence of the phenomenon and for clarification probe questions were used. For example: "Can you explain more? How? To create a clear picture of the social isolation of PCIMS the findings from interviewing the caregivers were explored by interviewing the viewpoint of the care-recipients and the healthcare providers who worked with them. The duration of the interviews was between 30 to 90 minutes.

Data Analysis

Data collection and analysis were carried out simultaneously. All interviews were audio-recorded and were transcript verbatim. First, in the open coding, concepts were formed with data fragmentation. Concepts, based on their similarities and differences, were placed in separate groups called categories. In axial coding analysis focused more on the paradigmatic model, and in this regard relationships between categories and sub-categories were defined. In selective coding, the categories were integrated and refined and the core variable was defined. Until the formation of a comprehensive relationship between theoretical concepts and the obtainment of theoretical saturation memoing and constant comparative analysis were iteratively used. In this condition data collection and analysis could be stopped [15].

Rigor

To increase credibility, prolonged engagement with the data and emerging codes and categories were used. Furthermore, transcripts with extracted codes were given to participants. The supplementary comments were collected and based on the essential changes were made. All steps in the research process, including codes and categories, for dependability and confirmability, were checked by supervisors. To ensure transferability, the process of collecting and analyzing data were comprehensively described [16].

Ethical Considerations

Before the interviews, all participants were informed that participating was completely voluntary in the study and they had the right to withdraw without any conditions at any stage of the study. Goals, importance, and protocol of the study were explained to all of the participants, and written informed consent was obtained. All participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. This study was part of a Ph.D. thesis and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR.REC.1395.398).

Results

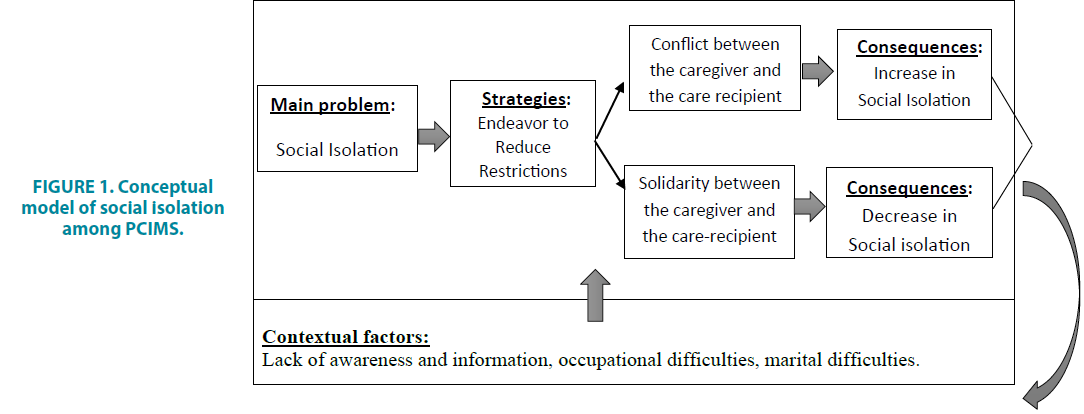

The current study, using grounded theory, presented a model exploring the process of social isolation of PCIMS (FIGURE 1). According to data analysis, "social isolation" is considered as the theme and the core variable. Other components of the model consist of four main categories that were included in this study. These categories are "lack of awareness and information", "occupational difficulties", "marital difficulties", and "endeavor to reduce restrictions”. TABLE 2 shows the theme, categories, and their sub-categories.

FIGURE 1. Conceptual model of social isolation among PCIMS.

| Theme | Categories | Sub-categories |

|---|---|---|

| Social isolation | Lack of awareness and information | Having no proper understanding of the disease’s entity |

| unsuitable notifications | ||

| unsuitable traditional and cultural beliefs | ||

| Occupational difficulties | barriers to participation in leisure activities | |

| Caregiver's sleep difficulties | ||

| Caregiver's work difficulties | ||

| Marital difficulties | couple quarrels | |

| Endeavor to Reduce Restrictions | Conflict between the caregiver and the care-recipient | |

| solidarity between the caregiver and the care-recipient |

TABLE 2. Theme, categories, and sub-categories of data.

■ Lack of awareness and information

Most of the participants complained about the lack or shortage of information regarding the illness. This lack of information ultimately led to relapse of the illness or an increase in disability of the care-recipient. Thus, by imposing excessive costs of treatment and caregiving burdens, indirectly, reduced the social communication of the caregivers. This category consists of three sub-categories which are " having no proper understanding of the disease’s entity", " unsuitable notifications", and " unsuitable traditional and cultural beliefs ".

■Having no proper understanding of the disease’s entity

Insufficient understanding of caregivers and care-recipients about this illness has caused them to have diagnostic doubts, and for a long while have unnecessary visits to different doctors in different cities for diagnoses. These visits burdened both the time and financial costs on the caregivers and indirectly caused a significant reduction in their social communications. A male parental caregiver said: "... Many relatives said that my daughter's symptoms are not similar to MS’s symptoms. For so long we had diagnostic doubt and went to various doctors in different cities. These visits were costly and time-consuming, which disrupted many of my social activities... (p15)."

■Unsuitable notifications

Participants sometimes acquire information, about the disease and its therapeutic methods, by having unsuitable Internet searches from invalid databases, which often caused an escalation in the care-recipients’ disabilities and the caregiving burden. A daughter caregiver stated: "…Due to the lack of suitable information about this illness, we tried to look for medical treatments on the Internet. Using these methods (such as strict diets) my mother’s disability and consequently, the caregiving burden increased, disrupting my social life in a way that I couldn’t even meet my friends for a long time ... (p6). "

■Unsuitable traditional and cultural beliefs

In the geographical context of this study, there are some traditional and cultural beliefs, such as belief in the existence of jinn (metaphysical and Transcendence entity) and its impact on the development of the disease through jinn possession. Some participants, due to the lack of awareness and information about this disease, identified possession as the cause of this illness. They visited spiritualists for treatment. A male spousal caregiver spoke as such about the prescription of a spiritualist for his wife: "... spiritualist prescribed that we must end our communication with all families who had a dead family member or had children under three years of age, these prescriptions restricted many of our communications (p4).

■Occupational difficulties

Several participating caregivers emphasized the impact of the illness on creating occupational difficulties for them, which in return has restricted their social communication. This category consists of three sub-categories which are " barriers to participation in leisure activities ", " Caregiver's sleep difficulties " and " Caregiver's work difficulties ".

■Barriers to participation in leisure activities

Some care-recipients, due to fluctuations in their health status as well as environmental barriers, could not participate in communitybased leisure activities. Therefore, caregivers were also forced to overlook these activities and were dissatisfied with this outcome. A female spousal care-recipient said: "My fluctuating health condition have canceled mine and my husband’s social leisure activity plans. He always nags about it ... (p19)." Another female parent caregiver said: "... During the illness’s relapse, my daughter is wheelchair-bounded, I cannot go to the park or shopping for fun, because there are no good routes for wheelchairs in buildings and through the city. I am forced to go nowhere in order to take care of her. In these situations, I really feel like a prisoner ... ( p5)."

Caregiver's Sleep Difficulties

Many care-recipients had night injection several times a week. These injections were accompanied by flu-like side effects, such as fever and severe headache. Therefore, their caregivers had to control these side effects. This night care indirectly, through lack of sleep, affected the PCIMS’s social activities. The participating neurologist said: “Several caregivers who accompany their care-recipients, in addition to the patient's problems, complained about lack of sleep because of night care due to patient's injection. They said that these lack of sleep disrupts their work and social life ... (p33)."

Caregiver's Work Difficulties

Many caregivers have said that taking care of an MS patient is time-consuming, and thus it has a significant impact on their work and their social communications. A male parent caregiver said: "... Caring for my daughter and the caring pressure from it has greatly affected my job. I do not have time and energy to work. Before I was more involved with work, connected with others, and had a sense of belonging. But now I sense isolation ... (p14)."

Marital Difficulties

In the geographical and cultural context of the study, the level of communication of others with a family depends on the level of intimacy in the relationship between the wife and the husband, and marital difficulties in a family reduce the communication of others with them. This category is comprised of a sub-category called Couple quarrels.

Couple Quarrels

Some spousal caregivers believed that the symptoms of illness, such as emotional lability and sexual dysfunction, have created conflicts and marital difficulties for them, thereby reduced their social communications.

A female spousal caregiver said: "Before the illness, my husband was very patient and kind. But after diagnoses, he is constantly agitated and quarrels with me. These quarrels have reduced the desire of friends and relatives to communicate with us, and this is painful ... (p9)." A male spousal caregiver said: "... because of my wife's sexual problems, we are just as two housemates. The psychological effects of this problem have caused arguments and quarrels, and as a family has less communication with friends and relatives ... ( p2)."

The three aforementioned categories formed the contextual factors. These factors caused the PCIMS to be directly or indirectly restricted and socially excluded. And so, their identity and sense of competence were disrupted and their sense of belonging to the society reduced. A female spousal caregiver said: "... The drastic decline in my relationships with others has made me feel no longer important to others as before, and cannot handle anything ... (p13)." And so, they consequently endeavored to reduce these restrictions.

Endeavor to Reduce Restrictions

In this category, action/interaction strategies and emotional responses are discussed, which caregivers have used in PCIMS social isolation process. This category consists of two subcategories which are "conflict between the caregiver and the care-recipient " and "solidarity between the caregiver and the care-recipient".

The Conflict between the Caregiver and the Care-recipient

Some caregivers took actions to reduce their restrictions and increase their social communication, in which they were only considerate toward their own restrictions, and the care-recipient and her/his concerns were usually neglected. One of these actions was the expansion of secret relationships with the same sex, such as friends, and with the opposite sex in the form of extramarital relations. A male spousal caregiver said: "... The decline in social communication and the marital problems made me try dependency on a secretive romantic relationship to reduce the psychological burdens of these restrictions (p2)." But these actions were usually not effective. The same spousal caregiver continued: "... In this secret relationship, I was constantly worried that someone would become aware of it, and so I became more distant from others. After a while, I suffered from guilt, anxiety, and isolation ... (p2). "These caregiver’s actions have prompted conflicting strategies of the care-recipients to control the new circumstances. One of these strategies was the deliberate increase in caregiver burden by the care-recipient. Another husband spousal caregiver said: "... I tried to have further secretive communications with my friends for a while, but after some time my wife noticed it and became suspicious, and by deliberately increasing the dependency and caregiving burdens made my social communications additionally restricted ... (p3)." Also, by smoking and using opioids some of the caregivers tried to reduce the psychological burden of reduction in their social communication. The participating psychologist said:" ... There are many referrals to the psychology section of MS society Center in which the caregivers due to use of opioids and smoking for reducing their caregiving psychological burden were addicted. This addiction has severely increased their family and social difficulties ... (p29)."

Solidarity between the Caregiver and the Care-recipient

Some caregivers gradually establish that solidarity with care-recipient could reduce their restrictions, including their social isolation. A male spousal caregiver said: "... over time, I realized that I need to use activities, which both of us agree on, to reduce my restrictions so that my wife would help me with it, and disagree less with them.... (p3)." The caregivers used activities that both partners actively and collaboratively participated in. In this regard, they also prevented the arousal of conflicting strategies. A male parent caregiver said: "... mountain climbing with our friends was one of the important activities of mine and my daughter’s. But after her diagnosis, we were forced to cancel it. Since both of us were very interested in movies, to retrieve the social communications we decided to go to the cinema with some of our friends on weekends... And now, on weekends, we enjoy being with our friends and watching a movie. (p15). The caregiver and the care recipient maintain the sense of acceptance and belonging to their friends by performing this collaborative activity. A number of PCIMS used activities to compensate for restrictions and increase their social communications, which initially only they were interested in and were carried out without the involvement of the care-recipients. Caregivers gradually by actively engaging the care recipients in these activities made them became interested in these activities and prevented the development of conflicting strategies of the care-recipients. These activities have contributed to enhancing the social communication of the PCIMS.

Another female spousal caregiver said: "... My husband did not go out of the house nor let me go or do anything. As a result, our financial problems were extreme and our social communication was very restricted. I decided to take steps to reduce these restrictions. So I used the facilities and loans that the government granted for agriculture and started farming. At first, my husband disagreed with this activity, but I tried to engage him in it. After some time, he was more interested than I was. … This collaborative activity has increased intimacy between us, as well as it increased our communications with others, and also made us feel competent and helpful ... (p10). “

Discussion

The findings from this study presented the first theory about the social isolation of PCIMS and describe the elements associated with contextual factors, strategies, and the consequences of the phenomenon.

The contextual factors of the present study were in consistency with the descriptive findings of some qualitative studies. For example, Abolhassani et al. in their qualitative study of the social impact of MS on these patients found that there was a lack of awareness in society about the illness, they also suggested the healthcare providers provide appropriate information about the disease to these patients and their families in order to minimize social problems faced by them [17]. Heward et al., in their grounded theory study in regard to occupational effects of caring for MS partners found that PCIMS had occupational constraints due to lack of time for leisure occupations and paid work [18]. Rollereau, in her grounded theory study regarding exploring the experience of men who care for a partner with MS, from the participants' statements concluded that caregiving of these patients was very timeconsuming and they consider it a full-time job that limited their leisure activities very much [19]. Several studies also believed that MS had a dramatic effect on couple relationships and could create significant marital problems [20]. The present study seeks to explore the social isolation process of PCIMS. In addition to describing contextual factors affecting this phenomenon, the strategies used by PCIMS to reduce these constraints as well as the consequences of these strategies were studied. Cheung and Hocking argued that PCIMS eventually finds the ability to adapt to care challenges [21]. In the present study, this conclusion was not true for all of the participants.

The present study, similar to Gulick's [22] study, showed that PCIMS uses both emotionalfocused and problem-focused strategies to cope with the challenges posed by MS. Some spousal caregivers have used actions such as extramarital relations and secret relationships to compensate for their lack of physical and emotional intimacy with their care-recipient and for the psychological effects of a decline in their social relationships (e.g. feeling of lack of belonging). On the other hand, care-recipients also used the deliberately increasing the caregiver burden strategy to control their caregivers. These strategies were conflicting and interrelated. Kouzoupis et al. also stated in their review study that MS could have different effects on all members of the family. As a result, to manage the condition they may use different coping strategies, which could be in conflict with each other and increase the caregiving burdens [23]. The romantic secretive relationships which can be seen in extramarital relations [24] can also create negative emotions such as fear and agitation, and affect the physical and psychological well-being [25]. In the present study, these relationships ultimately lead to a feeling of guilt, anxiety and further isolation. Some caregivers have tried to use smoking and opioids to reduce the psychological burden of social isolation, which in some cases led to addiction, and restricted their social communications. Stein et al. in their study stated that opioid systems play an important role in mediating the pain due to social isolation, such as affective distress which is caused by social isolation. But the persistence of social isolation can reduce the levels of endogenous opioids. Therefore, the individual may intend to compensate for this deficiency, by exogenous opioids substitution [26]. Cheung and Hocking believed that caregivers' personal meaning and concerns encourage them to overcome caregiving difficulties [21]. But the findings of this study showed that the shared meanings and concerns of these caregivers and care-recipients make them successful in reducing their constraints.

In the present study, some participating caregivers eventually concluded that in order to deal with constraints and to reduce social isolation, they should use dyadic actions that involve their care-recipients. The care-recipients concerns and needs should be considered in these activities. Therefore, these caregivers used collaborative activities, called "co-occupation". Co-occupations are activities that are performed by two or more people within the same time frame and have a degree of shared physicality, emotionality, and intentionality [27]. This study, like the study by Ono et al. [28], showed that primary caregivers can improve their wellbeing using co-occupations. Belonging is a basic requirement for all aspects of health and wellbeing [29,30], and in the present study, the use of co-occupations gives the caregivers a sense of belonging to society. Co-occupations, restored the identity of caregivers and increased their sense of competence, and adaptively reduced their social isolation.

Mutch in his qualitative study on the experience of spouses of individuals with MS, suggested to practitioners, in other to reduce the social isolation of these caregivers, it would be better that they and their care-recipients be assessed individually in order to resolve their personal problems [31]. In contrast, according to the findings of the present study, it would be recommended to the practitioners, especially occupational therapists to consider their mutual concerns and needs, and accordingly design appropriate co-occupations for them, in other to minimize their conflicting strategies and to improve the caregivers' social communication and well-being.

This study, like any study, has limitations. The experiences of volunteered participants in this study may be different from the experiences of other PCIMS who were not willing to participate in this study. As a result, this study may not cover the full range of experiences of PCIMS. On the other hand, due to the qualitative nature of the study the generalizability of its findings, beyond the geographic and cultural context of the study, is difficult. According to the findings of this research, cooccupations are of particular importance in improving the social communication of PCIMS and their compatibility with the caregiving role. Therefore, research needs to be done to explore the co-occupational experiences of these caregivers and the meaning of these cooccupations. In subsequent studies, researchers can clarify the dimensions of each of the categories in this study. They can also examine quantitative studies of the association between two or more concepts of this model.

Conclusion

This study explored the process of social isolation in PCIMS, and showed that these caregivers and their care-recipients, in an interactional manner are involved in creating this phenomenon (through contextual factors) as well as reducing it (through solidarity strategies). This was the first study to show that it is better to address their mutual needs and interests (not individually) in order to reduce the social isolation of these caregivers. Therefore, it is suggested that occupational therapists design co-occupations prevent the emergence of conflicting strategies to improve the social relationships of these caregivers and make them more compatible with their caregiving role. Also, other studies should be designed to translate this model into intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments and Funding

The authors thank the participants of this study for the time and effort they devoted to this project.

Competing and Conflicting Interests

The authors (s) have declared no potential conflict of interest with regard to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author’s Contribution

All authors contributed to this project and article equally. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Noorani N, Hadi F, Ahmadkhaniha HR. 29 year old man with multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia: A Case report. Electron. Physician. 8(12), 3409-3411 (2016).

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Barreto M, et al. Experiences of loneliness associated with being an informal caregiver: A qualitative investigation. Front Psychol. 8, 585 (2018).

- Petersen J, Kaye J, Jacobs PG, et al. Longitudinal relationship between loneliness and social isolation in older adults: Results from the cardiovascular health study. J. Aging Health. 28(5), 775-795(2016).

- Hasan M, Clark EM. I get so lonely, baby: The effects of loneliness and social isolation on romantic dependency. J. Soc. Psychol. 157(4), 429-444 (2017).

- Barth J, Schneider S, Von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 72(3), 229-238 (2010).

- Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Ann Intern. Med. 131(3), 165-173 (1999).

- Heffner KL, Waring ME, Roberts MB, Eaton CB, Gramling R. Social isolation, C-reactive protein, and coronary heart disease mortality among community-dwelling adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 72(9), 1482-1488 (2011).

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 241(4865), 540-550 (1988).

- Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. Jama. 311(10), 1052-1060 (2014).

- DesRosier MB, Catanzaro M, Piller J. Living with chronic illness: social support and the well spouse perspective. Rehabil. Nurs. 17(2), 87-91 (1992).

- Bogosian A, Moss-Morris R, Yardley L, Dennison L. Experiences of partners of people in the early stages of multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 5(7), 876-884 (2009).

- Boeije HR, Duijnstee MS, Grypdonck MH. Continuation of caregiving among partners who give total care to spouses with multiple sclerosis. Health Soc. Care Community. 11(3), 242-252 (2003).

- Bassi M, Falautano M, Cilia S, et al. Illness perception and well-being among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings. 23(1), 33-52 (2016).

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications. (2014).

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/104973239500500201

- Schwandt TA, Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Judging interpretations: But is it rigorous? trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation. 207(114), 11-25 (2007).

- Abolhassani S, Yazdannik A, Taleghani F, Zamani A. Social aspects of multiple sclerosis for Iranian individuals. Disabil. Rehabil. 37(4), 319-326 (2015).

- Heward K, Molineux M, Gough B. A grounded theory analysis of the occupational impact of caring for a partner who has multiple sclerosis. J. Occup. Sci. 13(2-3), 188-197 (2006).

- Rollero C. The experience of men caring for a partner with multiple sclerosis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 48(5), 482-489 (2016).

- Navidian A, Rezaee N, Baniasadi F, Shakiba M. Effect of a couples' relationship enrichment program on the quality of marital relationships from the perspective of spouses of patients with multiple sclerosis. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 238(9), 756-762 (2017).

- Cheung J, Hocking P. The experience of spousal carers of people with multiple sclerosis. Qual. Health Res. 14(2), 153-166 (2004).

- Gulick EE. Coping among spouses or significant others of persons with multiple sclerosis. Nursing res. 44(4), 220-225 (1995).

- Kouzoupis AB, Paparrigopoulos T, Soldatos M, Papadimitriou GN. The family of the multiple sclerosis patient: a psychosocial perspective. Int. Rev Psychiatry. 22(1), 83-89 (2010).

- Atkins DC, Eldridge KA, Baucom DH, Christensen A. Infidelity and behavioral couple therapy: optimism in the face of betrayal. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 73(1), 144-150 (2005).

- Lehmiller JJ. Secret romantic relationships: Consequences for personal and relational well-being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35(11), 1452-1466 (2000).

- Stein DJ, van Honk J, Ipser J, Solms M, Panksepp J. Opioids: from physical pain to the pain of social isolation. CNS Spectr. 12(9), 669-670 (2007).

- Pickens ND, Pizur-Barnekow K. Co-occupation: Extending the dialogue. J. Occupational Sci. 16(3), 151-156 (2009).

- Ono K, Kanayama Y, Iwata M, Yabuwaki K. Views on co-occupation between elderly persons with Dementia and family. J. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 3, 185 (2014).

- Hasselkus BR. The meaning of everyday occupation: SLACK. (2011).

- Khazaeian S, Kariman N, Ebadi A, Nasiri M. The impact of social capital and social support on the health of female-headed households: A systematic review. Electronic Physician. 9(12), 6027-6034 (2017).

- Mutch K. In sickness and in health: experience of caring for a spouse with MS. Br. J. Nurs. 19(4), 214-219 (2010).