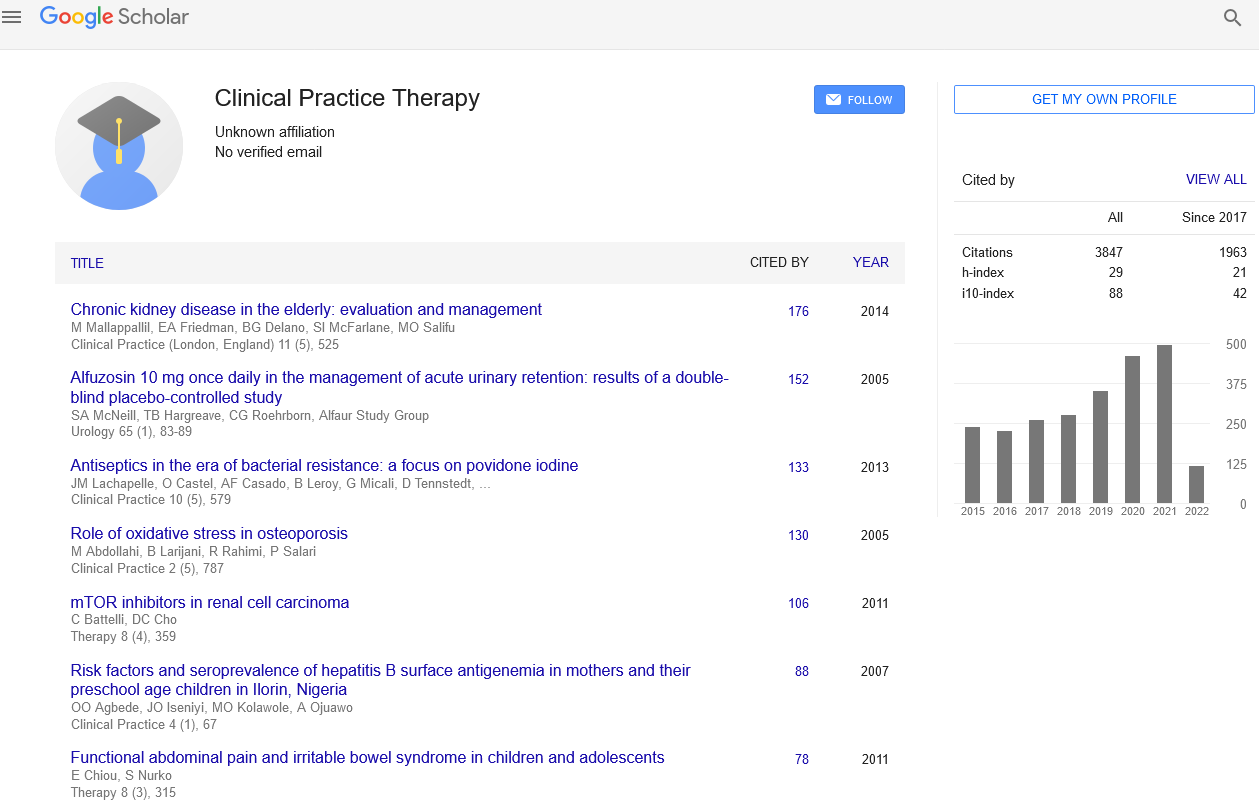

Opinion Article - Clinical Practice (2023) Volume 20, Issue 1

Does 'On Call' simulation training have a place in medical education programs?

- Corresponding Author:

- Anthony Lisacek Kiosoglous

Bronglais General Hospital, Aberystwyth Wales, United Kingdom

E-mail: Anthony@lkiosoglous.com

Received: 19 January, 2023, Manuscript No. fmcp-23-87436, Editor assigned: 21 January, 2023, PreQC No. fmcp-23-87436 (PQ), Reviewed: 28 January, 2023, QC No. fmcp-23-87436 (Q), Revised: 22 February, 2023, Manuscript No. fmcp-23-87436 (R), Published: 10 March, 2023, DOI. 10.37532/2044-9046.2023.20(1).

Abstract

There is a growing body of evidence newly qualified doctors feel underprepared for working “on-call” shifts. The aim of this paper is to discuss how final year medical students from both medical schools in Cardiff and Swansea University, Wales, United Kingdom benefited from a short 1-2 hour simulation based teaching program for on call / out of hours work. Fortyfour final year medical students completed a 1-2 hour on call simulation session at Bronglais General Hospital, Aberystwyth during their final year clinical placement. Students were treated and expected to perform as day 1 foundation year doctors in the UK. All students completed a questionnaire post workshop with the purpose of measuring subjectively what was gained and if they felt more confident attending their first set of on call shifts. As the feedback from the first few groups was excellent, the remaining students were asked an additional question before the workshop to determine how confident they felt attending an on call shift based on their current training. All students provided outstanding feedback from the simulation training stating they felt more confident with working on call. This was substantiated with 23 students average measure of confidence and safety pre-workshop to be 3/10, which increased to 7/10 post-workshop. All students reported they had not had formal independent training in being on call. The most common learning points for practice included better prioritisation and being clear with patient information and handover to seniors. This study gives testament to the growing body of literature that there may be a place for on call simulation training for undergraduate medical students that mimics the stressors of being on call

Keywords

simulation training • on call • foundation year 1 doctor • f1 doctor

Introduction

The transition from medical school to working as a foundation year doctor can be extremely daunting and stressful. Medical students in the United Kingdom often feel underprepared for working as junior doctors, often citing reasons related to lack of independent practical experience and managing uncertainty in emergency situations whilst working during on call shifts[1]. There is consistent evidence students want more experience of the actual role and daily duties of a Foundation year 1 (F1) doctor and on call experience[2-4] Medical students uniformly find performing activities that are similar to that of a junior doctor more suitable than simply shadowing or clerking patients[5]. Shadowing an F1 or senior doctor has been reported to not be enough to make the students feel safe at performing on call shifts independently [1]. Subsequently, attention has focused on junior doctors’ preparedness to practice, including shadowing schemes and the provision of effective induction and mandatory training in most hospitals.

Highlighted by the GMC in “outcomes for graduates” medical schools provide an education that allows newly qualified doctors to meet all the outcomes [6]. Medical students should take responsibility for their own learning and use the outcomes to understand what is expected of them by the time they graduate. Local education providers work with medical schools to provide clinical placements and learning opportunities that give medical students the opportunities to build practical experience and safely meet the outcomes [6].

Limitations of simulation on call training that have been reported in the literature include [7]:

• Small studies

• Intensity of resources in running

• A degree of additional strenuous cognitive load, imposed on students secondary to inauthentic features of the simulation. These include the use of manikins, students working in pairs and an observer following students at all times.

The Undergraduate and Postgraduate Education Department at Bronglais General Hospital, Aberystwyth, Wales, UK approved the design of a teaching program by local tutors for regional final year medical students to simulate being on call, as is expected of a F1 doctor. This was done to enhance the students experience and to assist with their transition from student to F1 doctors. Our initial pilot was with groups, but we found that there was one person who would take charge limiting the beneficial aspect for each individual medical student. Therefore, we quickly adapted the program so that students were independent on the ward to remove this limitation and ensure each student experiences the pressures of being on call [7].

The objectives of the teaching session for final year medical students expected to commence work within 12 months, included:

1. Assessment & management of acutely unwell patients 2

. Prioritising jobs in a busy and evolving environment

3. Communication (referrals, escalation, safeguarding concerns)

4. Understanding their own limitations when working independently

5. Development of non-technical skills 6. Correct documentation

No practical procedures were included in our program as this was not part of the learning outcomes. The aim of this report is to inform medical educators of the potential for on call simulation training in preparing final year medical students for working on call during their internships.

In order to gain feedback on the teaching session 23 of the 44 medical students were requested to answer the following question: How confident do you feel in handling an on call shift safely? Score 0-10 (0 indicates not at all safe or confident, 10 indicate safe and confident) (Figures 1-2). After each session a post workshop questionnaire was provided to all medical students, determining the effectiveness of the on-call simulation training and seeking feedback for the session itself. The student tutor ratio was 1:1 and the session ran for 2 hours in length and included multiple clinical presentations that can be encountered during a typical shift (day or night). Each student was contactable at all times via telephone (a fictitious bleep) which they were expected to answer when required. A senior was always available via telephone should the student have questions.

The students were informed prior to commencement of the scenarios of their role which included responding to bleeps, attending fictitious scenarios on the ward which involved multiple interactions with nursing, seniors, and liaising with other hospital professionals. Excluding tutors there was no human to patient / staff interaction to not compromise patient care. The plan was adapted to maintain a fixed level of education during the COVID pandemic and students were only directed to safe areas of the hospital, with no positive COVID-19 cases of which they were already undertaking their clinical placements.

Each student was contacted by a fictitious nurse, radiographer, senior, or referring doctor to see an acutely unwell patient, which was a written case in an envelope on the reception desk of a ward. Each case included patient concerns or nursing concerns, explanation of the case at hand, past medical history, the interpretation of recent blood results, relevant tests (e.g. ECG) and questions about how they would approach the scenario, what their differential diagnosis is, potential investigations, escalation and possible management. The students were deliberately contacted or ‘bleeped’ during their time interpreting the case at hand or whilst they were moving to the next scenario. It was here that the students were given more tasks than they would be able to handle at any given time to see how they adapted to a variety of events as if they were on call. Each student attended 3 out of 5 acutely unwell patient scenarios, but was tasked with 10 duties that required prioritising or managing over the phone in the space of an hour. If part of managing the patient involved contacting another health professional (e.g. the radiologist on-call) the student would need to contact them to request further investigations etc.

Following the session all students gathered in the postgraduate centre and individual feedback within a group setting was provided. All tutors would discuss how their students fared with regard to knowledge, communication and prioritisation. Focus was also shown on how well they managed the acutely unwell patients based on current guidelines and their knowledge of appropriate clinical decision tools, differential diagnosis, communication and telephone etiquette, prioritisation and whether escalation was at appropriate points in time. They were also informed of appropriate colleagues who could aid in their workload should they find themselves over-stretched. Documentation as is required legally was reviewed by tutors and individual feedback was given. Furthermore, students were given the opportunity to reflect on their own performance and ask questions pertinent to their future role as a F1 doctor at this point all concerns and queries were answered by clinical tutors.

The post workshop questionnaire included a series of questions (all anonymous) with the purpose of measuring subjectively what the students gained, and accordingly how the tutors could improve into the future. As seen in (FIGURE 3, FIGURE 4) all students found the workshop eneficial. A question asking whether students would be willing to be contacted once they had commenced work as a F1 doctor was included. If consent was given students provided their email address. The purpose of this question is to later determine whether this workshop provided them with a real-world confidence boost and for further validation of the effectiveness of such a program. This data has not yet been retrieved. Students were asked open ended questions to ascertain how they felt the course ran (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1. Post-workshop summary of student comments.

| Best things about the teaching were | “Actual real-life scenarios” |

|---|---|

| “The scenarios were all really realistic” | |

| “Accurate and applicable as if it was FY1” | |

| “Real time, useful cases, really useful to have a simulated on call with patients & the bleep going off. Was good to be able to work through scenarios for myself and get feedback on my management plans. Appreciated having one-on-one teaching and feedback.” | |

| “Good to practice fielding calls from wards while trying to do plans for patients, haven't had simulation of this previously.” | |

| The training could be improved by | Examples of out of hours clerking More cases Running another evening Full hands on ABCDE Scenario Clear explanations at start about what to expect. Comments pertaining to seeing real patients but understand that this is not possible. |

| Following this session, I will make the following changes to my practice | Better prioritization |

| Writing all jobs down | |

| Escalate earlier | |

| Thinking about the patient as a whole and exclude differentials. | |

| Ensure all details over phone are requested. | |

| Making sure I have all patient information when I get bleeped. | |

| Prioritize my jobs, and practice A-E with every examination. | |

| Document clearly, including that I have discussed with seniors. | |

| Put myself out there to practice | |

| Ensure I have adequate information to hand over to seniors. | |

| Ill be more assertive when prioritizing jobs | |

| I will be more specific with what I say | |

| Any topics that you want to learn about in future sessions? | 7 students requested ABCDE scenario practice. All students requested more sessions like this. 2 students requested more lectures. |

The outstanding feedback that is given to the numerous clinical educators evident in the literature gives testament to the fact “Oncall” scenarios would probably be beneficial to students at an undergraduate level. There is no replacement for real experience and whilst during the most demanding years of the medical school students are expected to hit the ground running, providing safe and optimum care for their patients. It is not possible to be 100% prepared for all scenarios but here we describe that putting students into a real world environment with real world challenges of unexpected scenarios and prioritisation may reduce students anxiety and stress levels associated with work as a future F1 doctor in the UK.

The preparedness a single 2 hour course can provide may reduce burden to trust doctors when new foundation doctors start working in August. The usefulness of the experience is evident from the student responses described both here and in the literature and is easily reproducible plus inexpensive as many junior doctors would also like to get involved in medical education.

A strength from this paper is that is has looked at more than one cohort of medical schools (both Cardiff and Swansea medical schools) and therefore provides data which suggests together with the literature that students nationwide would likely benefit from independent simulation in on-call scenarios prior to working as junior doctors. We recognize the limitations of our current study being at a small rural district general hospital in Aberystwyth Wales and the small sample size.

The authors believe that the addition of a group scenario such as a Medical Emergency Call where the students gather at the end or during would be beneficial in adding a different element to the optimum training for on-call scenarios. It is recommended that local medical educators include on-call simulation sessions at individual hospitals to reduce burden on trust doctors as newly graduated doctors may not work in the same hospital as where they did their undergraduate placements.

Conclusion

The observations from this small teaching programme gives testament that there is a place for on call simulation training for undergraduate medical students that mimics the stressors of being on call. Medical educators may wish to consider including a similar programme as an adjunct to other traditional curricular. Larger studies and literature reviews with longer term follow up data are required.

Acknowledgment

Many thanks to Dr.Sagar Sonanis, Dr.Maria Puthoor and Dr Mohamed A. Unais for acting as tutors and for their assistance with the workshops. Also, many thanks to the ongoing support of the Postgraduate and Undergraduate Medical Education Center at Bronglais General Hospital, Wales, United Kingdom.

Conflict of interest

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- Miles S, Kellett J, Leinster SJ. Medical graduates’ preparedness to practice: a comparison of undergraduate medical school training. BMC Med Educ. 1, 1-9 (2017).

- Dickinson M, Pimblett M, Hanson J, et al. Reflecting reality: Pager simulations in undergraduate education. Clin Teach. 11, 421-424 (2014).

- Manalayil J, Muston A, Ball A, et al. 1HR ON-CALL-Using Simulated ON-CALL to Underpin Experiential Learning in Final Year Medical Students. J Eur C. 91, 1832749 (2020).

- Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Med Educ. 445, 449-458 (2010).

- Vaughan L, McAlister G, Bell D. ‘August is always a nightmare’: results of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Society of Acute Medicine August transition survey. Clin Med. 11, 322 (2011).

- Gaskell N, Hinton R, Page T, et al. Putting an end to Black Wednesday: improving patient safety by achieving comprehensive trust induction and mandatory training by day 1. Clin Med. 2, 124 (2016).

- Hawkins N, Younan HC, Fyfe M, et al. Exploring why medical students still feel underprepared for clinical practice: a qualitative analysis of an authentic on‐call simulation. BMC Med Educ. 21, 01-11 (2021).