Short Communication - Clinical Practice (2020) Volume 17, Issue 4

Addressing delayed referral of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease from primary to specialty care

Abstract

Introduction

Given the nonspecific and heterogeneous presentation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), multiple and different healthcare providers may be involved in the diagnostic journey. Consequently, many patients experience delays in the diagnosis of their disease or are misdiagnosed with other conditions having symptoms that overlap with IBD, such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) [1]. Diagnostic delay in IBD is associated with poor clinical and treatment outcomes [1,2] impaired quality of life [2], and increased risk of intestinal surgery [3-5]. Additionally, early initiation of treatment was shown to improve the chances of treatment success [1]. Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that delayed diagnosis and treatment have detrimental implications on both patients and the healthcare system.

Studies from Europe and the US reported variable experiences for the time from symptom onset to IBD diagnosis, with values ranging between 5 and 9.5 months in Crohn’s disease (CD) [1,4-8] and between 1 and 5 months in Ulcerative Colitis (UC) [1,5-7]. The median time for a patient to be seen by a gastroenterologist was 7 months for CD and 3 months for UC in one study [5]. Interestingly, upon further dissection of the diagnostic pathway, one study showed that the median time for patients to seek medical advice (e.g. at primary care) following symptom onset ranged between 1-2 months [1,5] while the median time from initial physician visit to IBD diagnosis by a gastroenterologist ranged between 1 month for UC and 4 months for CD [1]. These observations suggest that a considerable delay is occurring not only for patients to attend to medical care, but also for them to be referred to a gastroenterologist after initial presentation at primary care. In fact, one study from Italy showed that a prior general Practitioner/Primary Care Physician (PCP) consultation is a significant and independent predictor for diagnostic delay in CD [8].

There could be various reasons to justify such referral delay from PCPs to gastroenterologists for patients with suspected IBD. One study from South Australia surveyed 1800 PCPs and showed that 37% reported being uncomfortable with IBD diagnosis and management [9]. A similar study from Saudi Arabia that surveyed 211 PCPs also concluded that the majority were uncomfortable with diagnosing and managing IBD, still, only half of them preferred to always refer the patient to a gastroenterologist [10]. In our clinical experience in the Middle East, such referral delay is commonly attributed to the time the PCP spends attempting to secure a diagnosis before going for a referral in the context of a complex condition and limited awareness, access or adherence to guidelines. Failure to reach a confirmed diagnosis also prompts patients to seek further advice from other PCPs causing further delay before a gastroenterologist is consulted. This results in a lack of continuity of care and in avoidable excessive healthcare expenditures. Moreover, PCPs do not always have access to appropriate tools to confirm the diagnosis and disease severity, and may end up treating ‘symptoms’ for a while until complications arise and the patient is referred to a gastroenterologist. In some countries in the Middle East, this is less apparent since the primary care system is not well established, and patients often present directly to specialist care. The downside of this is that specialist clinics become overcrowded with cases with simple ailments that could have been managed at PCP clinics.

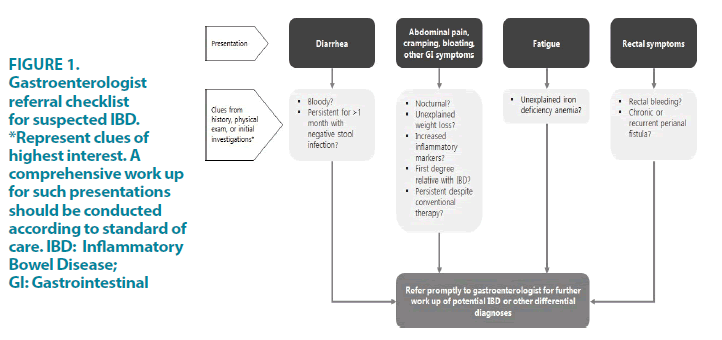

To avoid referral delays, as well as unnecessary over-referrals, we suggest that PCPs should still have a central yet well-defined role in the early detection of IBD and should not take much responsibility in confirming the diagnosis but rather in referring the patients to gastroenterologists when alarming gastrointestinal symptoms are observed. Although some ‘red flags’ and pathways for IBD referral have been identified and developed, these are often evident following a detailed diagnostic workup; while the focus here should be on trying to bring the relevant patient to the gastroenterologist’s attention earlier, before advanced investigations are performed. Moreover, given IBD’s nonspecific symptoms, it may be challenging for a PCP to review a checklist for IBD in specific without evaluating other disorders on the differential diagnosis. Thus, it may be more practical to have a checklist that includes key factors that indicate a patient requires a referral to a gastroenterologist in general. We herein propose such a checklist that can serve as a guide for PCPs to aid early referral of patients based on presenting signs and symptoms that may suggest a potential IBD diagnosis or other gastrointestinal diseases that require further diagnostic workup by a gastroenterologist (FIGURE 1). The checklist is based on common presentations of IBD but is not exclusive. PCPs should continue to refer patients with alternate presentations based on best judgment. The checklist is also not meant to include all scenarios where a gastroenterologist referral is required. PCPs should exercise best judgement of when referral is needed.

Moreover, a triage clinic has been proven effective in optimizing referrals by screening all presenting cases and only referring those imperatively needing specialist care. This can improve the flow between primary and specialty care and achieve earlier referral of IBD cases to gastroenterologists as soon as they present to PCPs. Some PCPs are often not aware of the negative consequences associated with delayed IBD diagnosis; thus, to further reinforce the checklist’s purpose, PCPs should be educated on the severity and impact of delayed diagnosis and informed about the importance of early referral at the inflammatory stage before the chronic damage has occurred. It is equally important to educate the patients on alarming signs and symptoms that would need evaluation by a gastroenterologist, and the acute, less concerning ones for which a PCP consultation would suffice.

While the aforementioned initiatives can improve timely and accurate diagnosis of IBD, there remains a clear lack of relevant records and databases that can evaluate the severity of the problem in various regions including the Middle East. These can serve as a baseline for measuring success in several measures such as reducing time to referral and diagnosis and impact on management outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Keyrouz of AMICULUM for medical editorial assistance. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Takeda Pharmaceuticals FZCO.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

Vito Annese has provided consultancies and/or paid lectures to Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring and Pfizer. Iyad Issa has received consultancies and/or lectures support from Abbvie, Takeda, Pfizer, Janssen and Abbott. Talal Al-Taweel has provided consultancies and/or paid lectures to Abbvie, Janssen, Ferring, Pfizer, Takeda and Tillots. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, et al. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 18, 496-505 (2012).

- Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Selvaggi F, et al. Delayed diagnosis is influenced by the clinical pattern of Crohn’s disease and affects treatment outcomes and quality of life in the long term: a cross-sectional study of 361 patients in Southern Italy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 27, 175-181 (2015).

- Lee DW, Koo JS, Choe JW, et al. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of intestinal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 23, 6474-6481 (2017).

- Nahon S, Lahmek P, Paupard T, et al. Diagnostic delay is associated with a greater risk of early surgery in a French cohort of Crohn's Disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 61, 3278-3284 (2016).

- Nguyen VQ, Jiang D, Hoffman SN, et al. Impact of diagnostic delay and associated factors on clinical outcomes in a U.S. inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 23, 1825-1831 (2017).

- Novacek G, Gröchenig HP, Haas T, et al. Diagnostic delay in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 131, 104-112 (2019).

- Zaharie R, Tantau A, Zaharie F, et al. Diagnostic delay in Romanian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Risk factors and impact on the disease course and need for surgery. J Crohns Colitis. 10, 306-314 (2016).

- Maconi G, Orlandinia L, Asthanab AK, et al. The impact of symptoms, irritable bowel syndrome pattern and diagnostic investigations on the diagnostic delay of Crohn's disease: A prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 47, 646-651 (2015).

- Tan M, Holloway RH, Lange K, et al. General practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes to inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med. 42, 801-807 (2012).

- Alharbi R, Almahmudi F, Makhdoom Y, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of primary healthcare physicians toward the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease following an educational intervention: A comparative analysis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 25, 277-285 (2019).